Globalization: Cultural Communication:

Cross-Cultural Communication in the Age of Globalization

Dr.

Andreas Eppink

Cultural

Anthropologist, Psychologist, Consultant

Malaga,

Spain

INTRODUCTION

Cultural differences can cause

substantial communication problems and misunderstanding on various levels. We

encounter these cultural differences daily with questions such as: “How can we

successfully negotiate this contract with our Chinese friends, considering both

our wish for efficiency, and their saving face?” “How can we improve the

service and assistance to ethnic minority clients?” “How can immigrants profit

more from the given opportunities in this country?” “Is intolerance an inherent

feature of Western, Eastern or other cultures?” Questions such as these are

abundant. In this article we will not deal specifically with these questions

themselves but with a theory on cultural differences and the impact on

cross-cultural communication.

CULTURE’S CONTINUITY

The universe, nature, cultures,

organizations, teams, relations in general, and individuals all possess common

characteristics in continuity. Always, this continuity is enhanced by ‘good

chemistry’, which means:

- complementing capabilities

- complementing goals

- the ‘right’ conditions.

Fig. 1: The continuity’s triangle of ‘good chemistry’.

The three never stay on their own.

An interrelation always exists between:

goals — capabilities — demands

(conditions), or

demands — goals — capabilities, or

capabilities — demands — goals.

WHAT IS CULTURE?

The term “culture” is used in

different ways. Rarely is the emphasis placed on the conditions in which people

(with the notable exceptions of the well-known anthropologist Oscar Lewis in

his study of “The Culture of Poverty”, which Paolo Freire called “The Culture of

Silence”).

Often a major emphasis in placed on

capabilities -- even exceptional capabilities -- as are illustrated in a

particular culture’s music, art, language, religion, or traditions, customs,

habits, etc. Generally, if we speak of “Arab”, Japanese”, or “Chinese culture”,

we mean language as our point of reference, while for “Confucian” or “Muslim

culture”, the reference point is philosophical or religious. The problem with

such generalizations is that invariably the many significant subcultures within

these cultures are over-looked. What, by example, should be understood by the

terms “American culture” or “European culture”? In “American culture” the

American-English language could be the feature, while with “European culture”

there is no similar commonality. In both cases we refer to the American or

European society, and their history.

In defining what culture is, the

reference to (a system of) “values” is more useful; however, concepts such as

values, norms, ideology, ethics, symbols, style (e.g. of leadership) are quite

abstract.

Some authors consider culture a way

to survive, or “the way in which people solve problems” . Although this

approach can be given credence, it is proposed here that the impact of goals

determines (at least to a significant degree) how people perceive reality and

strongly influences their ideas as to how problems can and should be solved. It

is at this point that we are back to values. The relation between goals and

values is strong, as people will follow goals according to their perceptions of

each stated goal’s value and importance, and thus values themselves tend to

become goals for many people. Some goals are formulated -- the so-called formal

goals -- but most are not, the informal goals. Both formal and informal goals have

their origins in basic psychological goals, for which the term Hidden Goals

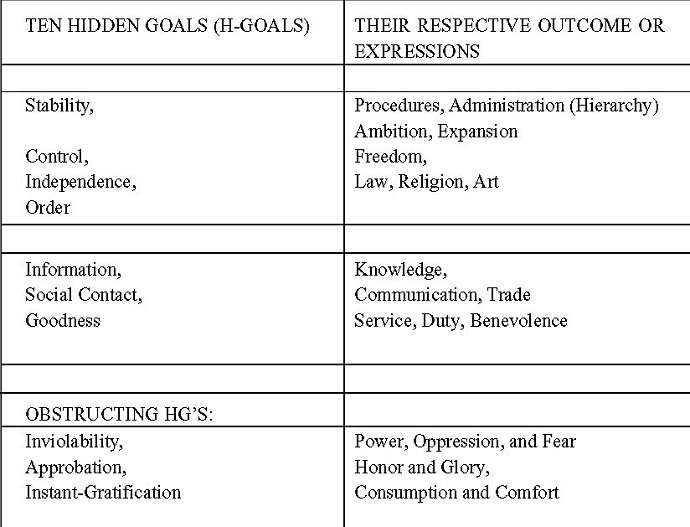

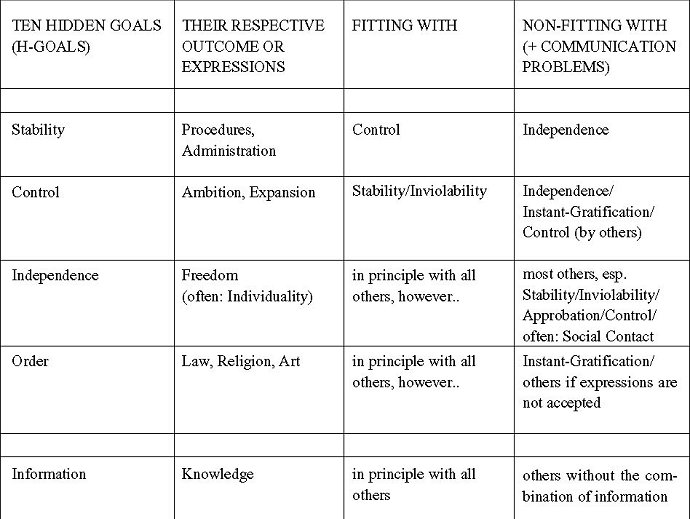

(HG’s) will be used herein (see chart on following page). . Here we will not

deal with the “why?” and “how?” of these ten (which have been derived them from

the famous classic Hindu scripture, Bhagavad Gita2). (Trompenaars,

1993)1

Cultures and subcultures can be

characterized by their accent on a (more or less) unique combination of H G ’s.

Because each individual follows all mentioned goals in life, and a group,

organization, or culture is formed by individuals, we will find the ten hidden

goals in each of them. Though, not to the same degree; the very variance in

degree and ranking of the H-goals ‘makes’ a culture. (Sub)cultural differences

can be explained by the quite infinite combination possibilities of the HG’s,

in relation to the two formerly mentioned other elements of continuity:

capabilities and conditions (circumstances in time and space3). One

H-goal, or the combination of several, may dominate within a culture (with small

changes in time and circumstances). Within a society, cultural expressions and

productions --such as art, customs, religion and social life in general --are

variations which can defined within a specific combination of HG’s . The ten

Hidden Goals and their outcome are here summarized in key words:

CULTURAL CHANGE

If the ranking of any particular HG

(or combination of HG’s) changes, then a corresponding culture change occurs as

well. Change is inherent in nature (and culture) for three reasons. First,

because all HG’s are implicated (i.e. as the HG’s are not all compatible, some

degree of struggle occurs between the followers, particularly if obstructing

goals are involved). Secondly, change also occurs if new capabilities are

developed, thereby presenting a new set of circumstances and demands and the

resultant rise or fall of a particular HG’s ranking (in the last century we

have seen amazing cultural changes in Western, Japanese and other Asian

cultures as the Information HG rose, and as education became increasingly

available).

The third reason why cultures

inevitably change are external circumstances and influences; these influences

cause changes both in HG-ranking and in overall capabilities (however not all

changes mean discontinuity; remembering that the primary function of culture is

the survival of its participants, we can speak of discontinuity if a culture’s

participants suffer distress and harm, and cannot survive).4

Certain goals can be deemed

“obstructing” if they can never be reached by effort; a culture’s striving to

reach unattainable goals inevitably leads to distortions in reality perception,

which in turn causes discontinuity. Recognizing the fact that obstructing HG’s

are inherent in life, some discontinuity can never be avoided. In the most

extreme cases, if obstructing HG’s rise high in ranking the culture will

collapse, (as occurred in the final period of the Roman Empire and the

communist cultures of the late 1980’s). Due to a restricted point of view

provoked by obstructing goals, most capabilities are developed limitedly or

one-sidedly, while others are bluntly restricted. The resultant negative

economic impact will be clear.

POINT OF VIEW AND COMMUNICATION

For the first time in history the

United States House of Representatives was shut down to allow health

authorities to check for traces of anthrax. House members were widely

criticized for leaving while the Senate remained in session. The members of the

House even were called “weaklings”. “The unprecedented move underscored the

pressure lawmakers are under to demonstrate they can conduct the nation’s

legislative business during a time of crisis." So could be read in the

Washington papers.5

The judgment of the different

behaviors of the House and Senate members will depend upon each particular

individual’s point of view: Duty, (safety-) Procedures, or Fear.

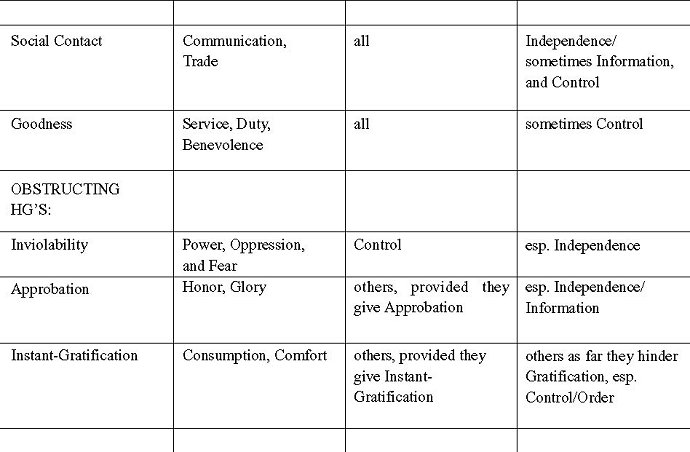

The variety of points of view, or

frames of reference between and within cultures, is reflected within the

various rankings of the various HG’s (or combinations thereof). These

differences ultimately cause the difficulties of communication and

understanding which this article addresses.

The following points can be useful

in understanding cultural differences, cultural discrepancies and

(in)compatibility, in terms of cross-cultural communication:

Most cultures, and particularly

subcultures, tend to accentuate one point of view originated from one HG (or a

combination of a few). Communication is essentially translating content into terms

of the HG’s of the cultural audience with which one desires to engage in

dialog. “Good communication” essentially signifies an accurate matching of

HG’s. If one interprets that words or sentences, as such, mean what they say,

one is (only) referring to the HG Information, which often appears to be (but

in reality may not be) As a case in point, the newspapers of former communist

countries - and still in totalitarian states - one must still read beyond the

words in order to hope to grasp some degree of knowledge of what is actually

occurring.

The Information HG most commonly

appears in combination with -- and is resultantly overruled by --one or more of

the other HG’s. Therefore, within cross-cultural communication a simple literal

translation will not suffice. The most convenient example is obtained by a look

at the various cultural implications of the basic word “yes”. “Yes” can mean: I

agree with you; I understand you (but this doesn’t automatically imply I agree

with you); I hear you (which doesn’t automatically imply I understand you);

and: I agree and accept the consequences, or I agree and will obey you. What

the real significance of “yes” is varies with the underlying combination of

HG’s.

UNDERSTANDING OTHER CULTURES

Generally speaking, within a culture

misunderstanding is avoided because of the existence of commonly-shared HG’s.

Between participants of different cultures, however, misinterpretation can

easily arise.

Such an example of misinterpretation

concerns the concept of “saving face”, a primary value in Asian and other

cultures. To save face can take various forms, all of which have in common the

intent to avoid offending or appearing to be brusque to others. Smiling under

all circumstances, even if one does not agree or even if one is hurt, is one

form, which by Westerners is interpreted as happiness or agreement. The act of

saving face is mainly based upon the HG-combination of Stability and Goodness

(particularly the sub-factors Duty and Benevolence); Westerners are able to

correct their misinterpretation to the extent that they are familiar with

politeness (that being a weaker pronounced expression of the same

HG-combination). However, not all Westerners will make this correction; in some

Western subcultures the Independence HG (and individual Freedom) predominates;

from this point of view, politeness and saving face are considered mere

old-fashioned, dishonest, relics of a past culture (while conversely, some

Asians, overlooking the Independence HG, will think of Westerners as barbarians).

Much is said about mutual cultural

understanding and mutual acceptance. This idea as such can be interpreted from

various HG’s, including Independence, Goodness, Information, or Social Contact,

and can take corresponding forms. The other HG’s, however, will never allow

that tolerance, and thus mutual acceptance of other cultures can never be fully

realized (nor can cultural relativity in the concept that “all cultures are

equal”). In example, from the point of view of the Control HG -- and to some

extent the Independence HG -- expansion, development, (personal) ambition, and

even “righteous” wars can be tolerated. Within the frame of reference provoked

by other HG’s, particularly Goodness, Stability, and Order, even” righteous”

forms of aggression are far less tolerated

Mutual acceptance is quite difficult

if dominating HG’s differ between (participants of) cultures; this is

especially the case if one or more of the obstructing HG’s take a pronounced

place. In example, to save face, as an expression of Stability-Goodness

combined with Approbation, will produce an intolerant Honor code that refuses

all that is deviant or ‘alien’. (Goodness will be narrowly interpreted, and

restricted to what “my people” think is good.). Xenophobia, racism, and an

array of other forms of intolerance prevail by the Honor code, which can be

encountered in Western, Arab, and Asian cultures, as well as within a number of

subcultures.

Blood vengeance; oppression of

women, children and other (ethnic or religious) minorities; a significant power

distance based on wealth, caste, class or status can all being defended by

culture-participants as their inalienable cultural marks. Such cultural

attributes are the outcome of dominating obstructing HG’s. If obstructing goals

dominate, the view of a culture’s participants is limited, and by consequence

the interests (HG’s) of others are disregarded.

CONCLUSIONS:

* Not all individuals follow the

same HG’s.

* Different (combinations of) HG’s

cause different points of view, and sub-cultural differences.

* Communicating with others means

translating the message in terms of the other’s HG’s.

* Understanding other cultures is to

understand their principal HG’s.

* To understand does not necessarily

indicate or require acceptance (no one can accept the expressions of other’s

HG’s if these are conflicting with one’s own HG’s).

The first characteristic of the

current era is the still-growing extension of information exchange. Thus, in

all societies the Information HG will rise in ranking and influence, will

continue to change cultures, and will continue to make the world more open.

With a true cross-cultural understanding, the world’s minority cultures can not

only survive, they can find all the information necessary to thrive. In fact,

the very characteristic of an enlightened ‘free world’ is the existence and

success of de facto minorities.

1 “Culture” is in this case considered a so-called

contingency factor, and as a determinant factor as well, also primarily an

interaction between conditions and capabilities.

2 Hinduism stated that all things are in continuous

transformation by the three Gunas: mass, movement, and harmony, each of which

is necessarily subordinated to the relation of both others. Human beings can be

characterized by four ‘works’(originally flexible, later fossilized into the

four castes). The four ‘works’ in combination with the three Gunas make twelve

basic constellations, here called Hidden Goals, and for simplicity sake reduced

to ten.

3 Hinduism includes in circumstances of space and time:

birth- origin, term of life, and experience.

4 Symptoms of discontinuity are: unrest, internal discord,

conflicts or “tribal wars”, crisis, “rot in the top”, financial-economical or

other “problems”, undesired take-over, losses, bankruptcy, dissolution; and on

the individual level: distress, harm, and hurt. Symptoms of continuity are:

survival, cohesion and alliances, well-being, growth, flexibility, innovation

and adaptation to new circumstances.

5 Quotation: Washington Post.

6 Watzlawick distinguishes between two communication levels:

that of the literal meaning (content level) and the relational level e.g. power

distance - of those who communicate with each other. Bateson’s remark that a

geographical map is only a representation of reality applies to words and

sentences too. Bernstein, and Douglas, speak of implicit and explicit

communication codes.

BWW

Society Member Dr. Andreas Eppink received his Doctorate degree in Social

Sciences in 1977 from the University of Amsterdam, went on to study Clinical

Psychology, and was officially registered as a Psychotherapist. He has worked

as a Management Consultant, especially in the television, advertising, daily

press, family business, transport, and public administration sectors, including

work with the town of Maastricht. Prior to this, as an Anthropologist

specializing in the study of culture, Dr. Eppink was a pioneer in the field of migration

study, in particular mental health and occupation. In 1971 he founded the

Averroes Foundation for the study of these areas. He headed this institute from

1978 to 1983, as it then became state run. He was an intergovernmental expert

of the European Committee for Migration in Geneva, a member of the Board of

Advisors to the Dutch Minister of the Interior, and an expert with different

European committees in Strasbourg and Brussels. Dr. Eppink speaks five

languages and reads several more.

[ BWW Society Home Page ]

© 2016 The Bibliotheque: World Wide Society