|

BACKGROUND

It is assumed that readers are familiar with Part 1 of this course in Macro-economic

Design. In Part 1

it was explained why the traditional model used for Housing Finance

destabilises economies and in particular the one third of some economies that

makes up the housing based sectors. The concept of National Average Earnings,

NAE, was explained as being a measure of debt. It makes more sense to count the

number of NAE that a person has saved / lent / borrowed than to count the

money. It was explained that if wages / NAE increase at AEG% p.a. and there is

interest payable in excess of this AEG% figure, then the debt rises because the

additional interest, called the true rate of interest, I%, adds more NAE to the

amount of NAE that had been borrowed / lent.

We had the equation I% = r% - AEG% where I% is the true rate of interest, r% is the nominal rate of interest (usually called the rate of interest), and AEG% is the rate at which Average earnings / wages / incomes are rising.

WHAT IS A BOND?

Governments (and others) issue bonds and people and financial institutions buy (invest in) them. The issuer of bonds is a borrower that pays an interest coupon periodically. Savers and financial institutions buy into this kind of investment / debt. In return they get interest on their money and they get their money back at the maturity date which may be a few years, or many years into the future.

THE FIXED INTEREST BOND PROBLEM

The problem with fixed interest bonds is that they perpetuate what economists call ‘The Money Illusion.’ This is the illusory idea that repaying the money is the same thing as repaying the debt.

If on average everyone gets a wage rise of say 4% (the rate of AEG% p.a.), and if no interest or capital is added to their debts, then on average, people can repay their debts around 4% more quickly: it takes around 4% fewer working hours. The lender / saver loses some of the NAE that they have saved and invested / lent.

In order to neutralise this cost reduction, 4% (that is AEG%), needs to be added to the debt. Because AEG% p.a. varies, and could be even 10%, using a fixed interest rate of say 4% to add interest to the debt does not work. It can be too much or too little.

When we look at savers, if get that 4% interest and you spend it as income, then you are spending that 4%, AEG%, of your saved capital. You are spending 4% of the NAE that you have saved.

Furthermore the tax system is wrong. You will be paying tax on that 4% interest. This is a tax on your capital, not on your actual income. The income is anything above that 4%.

People that borrow for home loans or for other purposes can also get a fixed rate of interest for a period. In the USA that can be up to 30 years. The problem for borrowers comes if incomes are falling. A fixed cost and falling income is not a good idea either for borrowers or for lenders trying to recover the money / NAE that they have lent. And it is not good for aggregate spending in the economy, which will reduce causing employment levels to fall.

Either way, if inflation is rising or falling, if a fixed rate of interest is used, problems are created.

We need a new form of bond and tax freedom on AEG% interest, a new kind of bond that does not provide us with such unnecessary, destabilising problems.

THE REAL COST OF BORROWING

If you are a government intent on reducing the rate of inflation, and if this also means reducing the rate of AEG% p.a. (wages inflation / earnings inflation), then every 1% fall in AEG% will add 1% more NAE to the amount of your tax payers’ debt.

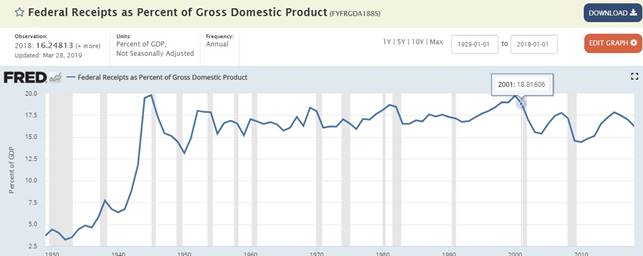

When, in the USA in the 1980s and 1990s, under Paul Volker’s chairmanship of the Federal Reserve Bank, inflation was reduced, the value of fixed interest debt owed by the US Treasury ultimately cost something like 9% true interest because of the success in reducing the level of AEG%. Given that the debt was initially around half a GDP of the USA economy, the total cost was, on average, around 4.5% of a GDP p.a. over the 20 year period.

That is something like the equivalent of 26% of the annual receipts obtained from the population by the Federal Government. Bill Gross famously made a fortune by buying this Federal Debt for his managed fund. Without even trying, he could have made a return of AEG% + 9% p.a. on his early investments.

In the reverse scenario, when governments allow inflation rates to rise they reduce their debt. But there is a cost. When savings invested in government debt and in other fixed interest debt, are falling in value, people feel a need to save more. That is what they do. So aggregate spending in the economy slows, government revenues fall, and investment reduces. There may be a recession. All of this damages the rate of growth of the economy and can threaten the level of employment.

Either way, fixed interest government debt and other fixed interest debt is damaging.

There are other economic costs associated with fixed interest bonds.

For example, they are used as a part of the reserves of lenders and insurance companies. When interest rates rise to slow borrowing appetite and when this results in arrears and foreclosures, lenders have very high costs. Some may not survive, especially if property values fall as they may well do as explained in Part 1. The situation is worsened by the falling market value of the reserves that they hold in fixed interest bonds and other invested assets. Their costs rise and their fixed interest bond reserves and other investments fall in value at the very time that they are most needed. Reserves are supposed to be there to avoid such a scenario. Other forms of investment in equities and property cannot do that.

POTENTIAL SOLUTIONS

For another example, insurance companies insure events that may not happen for decades, like storm damage, fires, and crop failures. They take monthly payments in return for the future insurance cover that they provide, and they need a safe place to invest the money as a reserve fund for meeting those future claims. A bond whose value rises at the same pace as NAE or at AEG% p.a. would do nicely. It will rise at a rate quite similar to the rising value of possible future claims.

For a third example, pension funds try to offer a retirement income that is in some way related to the final salary of its members / subscribers. What they need is to invest the premiums paid in an asset that will rise at the same rate as NAE / Wages. A fixed Interest Bond does not do that. It may pay more or it may pay less. This is a risk to the pension fund that it should not need to take. A lot of big companies like Shell Oil for example owe their pension funds billions of dollars because their investments have not performed well enough. Those companies could have made better use of this money.

As a fourth example, lenders also need an asset for their reserves that rises as NAE increases because as NAE rises they can and they do lend more against those higher incomes. The amount of their exposure to risk / losses, rises at that same AEG% p.a. kind of rate. Remember, AEG% p.a. is the rate of increase of NAE.

SOLUTIONS

Governments wishing to avoid those high costs of fighting inflation or those high costs of damaging savings can do so by avoiding the use of fixed interest bonds to fund their debt. The way forward is to borrow using bonds whose capital value is index-linked to NAE.

If they issue debt instruments (bonds) that have the capital value index-linked to NAE then there is no risk to the fiscus from reducing inflation and no risk to the overall economy from moderately rising inflation.

A government backed bond that has its capital index-linked to NAE is a risk free asset in the eyes of pension funds, lenders, insurers, and savers. All government and private sector inflation-linked risks are covered. There is a huge untapped market out there for investing in NAE-linked bonds. The larger the market for debt / bonds, the cheaper it is for a government to borrow. The same applies to commerce. The larger the market for NAE-linked bonds, the more they too can borrow. And by borrowing in such a way, they can avoid the cash flow problems of having to borrow interest to pay interest. More of what they borrow can be invested. The cost saving rises as the level of inflation rises because more of the interest rate can be rolled up inside the bond, and just added to the capital debt. That debt will then rise at AEG% minus any payments made. But so too will the turnover and profits of many businesses. As incomes rise there is more spending. Under Part 1, property values, used for collateral may also rise at that same rate. Those ILS mortgage models can work in partnership with these bonds very nicely.

In addition to the foregoing list of potential investors there are manages funds like Unit Trusts and ETFs. Investors in property and equities that normally seek to benefit from the growth of national average spending and the resulting growth of business profits, may want to have a proportion of any investment that they make invested in NAE-linked Bonds. Sales of Managed funds rise when they fill a gap in the savings and investments market. Gaps appear when a managed fund looks too risky, and they can also appear when a managed fund looks too safe. Different investors want different risk exposure levels but they still want to have an asset that rises with NAE. So managed funds will buy these NAE-linked bonds to manage the level of risk that they are offering to investors.

There is another way in which governments can benefit from using NAE-linked bonds as a borrowing instrument. Unlike fixed interest bonds, a risk free asset does not have to pay what is called a ‘risk premium.’ That is an additional rate of interest to offset the risk faced by investors such as pension funds, insurance companies, etc., that buy the bonds. The level of risk contained in a fixed interest bond can be anything, and the longer the lifetime of the bond the greater the risk. This discourages governments and commerce from issuing or buying long term fixed interest bonds. Short term bonds are difficult to use because, for example, a government will shortly have to repay that money and issue a new fixed interest bond. A bank that issues a short term bond must find short term borrowers, or simply use that money for liquidity and current expenditure like an overdraft. Short repayment terms are very costly to repay. Not a lot can be lent that way. But a long term NAE-linked bond can be a very attractive form of debt with little administrative cost. The bond does not need to be repaid and replaced for a very long time. Any difficulties faced by a government over its ability to service its rising debt can be more easily managed if it does not have to re-borrow its existing debt every two or three years.

A bond whose capital is index linked to NAE can live forever without losing its underlying market value, provided that the borrower servicing the debt continues to exist. This is why government debt that is index linked to NAE would be the most risk free investment that mankind is ever likely to see. This is why a 1% interest rate coupon that is paid by government / national treasury to managed funds and pension funds would cover their administration costs, allowing these funds to offer a risk free savings and investment plan to their subscribers. That would remove the risk premium that governments must normally pay on their Sovereign Debt.

Currently, the world of debt and of interest rates is very abnormal. Interest rates in some nations are too low and too expensive to economic growth. In a healthy economy, as explained in Part 1 hereof.

COST OF DEBT COMPARISONS

The cheapest rate that a prime mortgage can offer to borrowers is around a 3% true rate of interest. That is 3% more than AEG% p.a. By paying only 1% interest, on a risk free bond linked to NAE, and by having no risk premium to pay, this might save up to 2% of the cost of sovereign debt. Sovereign debt (government debt) is measured in fractions of GDP, or in some cases it can be a multiple of GDP. Saving 2% interest on one GDP of sovereign debt could reduce the rate of VAT or of income tax by 6% or more. This three times multiplier is because government revenues are normally around one third of GDP or less. In some cases it could be more than 6% added to VAT.

CONCLUSION

Overall savings can be enough to boost economic growth significantly. It can reduce risk to lenders, savers, insurers, and pension funds and it can reduce the risk of recessions. For marketing / savings purposes these bonds have been dubbed ‘Wealth Bonds.’ They protect wealth.

FURTHER OBSERVATIONS

The ILS model for safe lending as already explained in the Part 1 video, can stabilise a third of an economy, significantly boosting economic growth and the construction and banking sectors. Wealth Bonds will add a further boost to that level of economic and financial stability, further boosting economic growth / output. Note: there is no guarantee that economic growth will always be possible because the earth has limited resources. But optimising economic output based upon the resources that are available is an objective that can be achieved. This is what macro-economic design is all about. But governments must remain free to decide how they want to allocate the revenues that they gather. It’s just easier to win the next election when the economy is performing well. So they have an interest in promoting this new science of macro-economic design.

In both cases, by using the ILS model for lending and savings and by using wealth bonds for raising money, the most significant difficulties of managing interest rates by the central banks are removed. So the economy becomes easier to manage, boosting sustainable economic output through better and easier management of credit and of inflation.

That makes three ways to boost employment and economic output:

1. More stable property sector,

2. Cheaper and safer borrowing using wealth bonds, and

3. Easier management of monetary policy.

Added confidence also helps.

THE LOW INFLATION TRAP

In the case of the Federal Reserve Bank, the Bank of England, and other similar central banks, the biggest problem that they face is raising interest rates without harming their economies. They know that not raising rates is significantly harming their economies. And with low inflation, low AEG% people cannot cope with rising debt costs. So with the aid of these new instruments for finance and debt, there is a way forward to be explored. Debt costs on existing debt do not rise. On housing finance they fall. These new debt instruments clear the way forward for raising interest rates when needed. The writer can discuss some of the difficulties and the options available to policy makers. Cheaper government borrowing and better growth of economic output increase the options for government to subsidise those in need, including the governments themselves.

All of the above are reasons why the new science of macro-economic design may earn a Nobel Prize Nomination from two university professors so far. The offer was made some time ago and would be conditional upon some real progress being made in a tangible way or as an academic presentation, yet to be done. Currently most of the information is only posted on websites and You Tube. But there is also a privately published book entitled, “What is the Ingram School of Economics? And why is it essential?”

In this book the subject is extended to the introduction of new instruments for the management of an economy.

We will make a start on that in Part 3 of this course.

As an introduction to it, readers may like to view this You Tube Video. It is a brief extract of a lecture given to a university on how to end the financial crisis of 2008. The presentation was given at around that time. The USA authorities were told by an Actuarial Analyst with one of the world’s top four consultancies, that an academically sound solution to the crisis does exist but they took no notice. Both the Federal Reserve and the World Bank say they are not willing to view material from a non academic source. The then professor of accounting at the university of Pretoria, Jean Myburgh, on looking at Part 1 of this course said, “Are they mad?”

A Note on Membership in the BWW Society-Institute for Positive Global Solutions: Standard Membership requires an academic level of at least Associate Professor (or the equivalent in non-academic fields); Fellowship Status is reserved for Full Professors or equivalent.