The Thriving of Culture: A Culture-Enhancing Theory of Flourishing Employment

By Professor Kensei Hiwaki, Tokyo International University

Is it possible that we are standing upon the doorstep to a New Age of Enlightenment? Although this may be difficult to fathom in today’s world, this New Age of Enlightenment holds the promise of a sharing of the world’s wealth and technology, the creation of new opportunities for education and success within the world’s underdeveloped nations, and the emergence of the cognitive fact that, over the long-term, all humankind must thrive in order for any of us to thrive. Professor Kensei Hiwaki presents a solid basis for viewing culture — whether regional, national, ethnic or even tribal — as a critical ele ment, the protection, nurturing and enhancement of which is necessary for the long-term success of traditional market forces.

The issue of employment is most relevant to cultural value and diversity, since broadly defined cultures of different societies are generally embodied in their respective work-forces. It is the cultural contents of these work-forces that comprise their general capabilities in production and other socioeconomic activities. Such general capabilities, in turn, facilitate market- oriented activities, for it is a truism that market functions on a broadly- defined cultural foundation. Nevertheless, the market treats abundant commodity as “free goods” and exploits them thoroughly to the point that practically no room is left for their conservation or restoration. Thus, the very abundance of culture-worthy general capabilities works against these capabilities within the market, giving rise to a serious paradox: market tends to degrade the value of culture and eventually obliterate the long-accumulated cultural foundation that is essential for market activities to continue and expand. Perhaps, this paradox suggests a fundamental flaw of market (not just the level of “market failure”) and, for that matter, possibly a fatal flaw of the modern economics that relies heavily upon a free and competitive market.

For market is the very cause of on-going cultural and environmental devastation. Put differently, the very short-sighted (not long-sighted) and flow-oriented (not stock-oriented) ethos of market leads cultures and environments to their eventual collapse, despite the fact that their existence is most essential to human life, socioeconomic development and the continuation of market activities. Rectifying the undesirable course toward a cultural obliteration, as well as toward an eventual dead end to market activities, may require, among other things, a culture-enhancing employment system that leads to a harmonious and synergistic interaction between culture and market for enriching culture and augmenting market, also indirectly contributing to the conservation of the global environment. Such interaction is the focal point in our present introduction of a culture-enriching approach to employment. The key words and central ideas presented here concern the concepts of all-encompassing culture, cultural foundation, culture-effective skills, market-effective skills, competitive employment, and culture-enhancing employment.

CULTURE VERSUS MARKET

The theoretical approach to free and competitive market goes back to the publication of The Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith in 1776 [Smith, 1937]. Western societies, regardless of understanding Adam Smith correctly or not, have largely adapted themselves to the way of thinking based on the politicoeconomic concepts of the “invisible hand” (free and competitive market) and “self-interest” (simplistic

human nature). And, their economists have eagerly spread the thought throughout nearly the entire world. These two concepts together have drastically degraded cultural values in many societies by rewarding the market- related values and upholding a competitive model of employment. Under such a model the shortsighted market naturally underestimates cultural contents in human activities, rewarding mostly market-demanded skills, while paying little attention to the cultural role which is indispensable for market transactions. This denigration of cultural worth may result in a shrinking cultural foundation, upon which newly demanded skills of lopsided sophistication are to be formed by an increasingly smaller proportion of people, thus inducing socioeconomic polarization and politicoeconomic animosity.

An all-encompassing culture (simply, “Culture”), representing the cumulative endeavors of people in numerous generations to weave together a great variety of social fabrics in time and space, is construed here as one having a desirable tendency to enrich itself over time, and simultaneously work toward general peace and comfort of the people. This interpretation of Culture emphasizes the keynote of Culture, namely, the cultural inclination toward peace. This rather simplistic statement of cultural tendency is useful for contrasting Culture with Market in their basic characteristics. We assume that Culture calls for a long-term, cooperative, inward-looking and stock-oriented ethos, while Market emphasizes a short-term, competitive, outward-looking and flow-oriented ethos. In my opinion, a harmonious and synergistic interaction between Culture and Market conduces to a culture of peace and a well-balanced socioeconomic development. For such synergistic interaction, our long-term model of employment that encompasses the joint characteristics of Culture and Market may offer a useful analytical tool as well as meaningful policy implications.

To be sure, any employment practices must consider the cultural backgrounds of respective societies to function reasonably well. The arrival of modern industrial societies, however, induced a gradual abstraction of labor from the underlying Culture to simulate the ideal of Market that is deemed totally dependent upon demand and supply under the assumption of perfect competition. “The broad argument is that, given free and informed competition among workers and employers, each worker must be paid the value of his contribution to production” [Reynolds, 1978]. This idealized model of employment assumes, among other things, that many small employers competing for labor, with no collusion among employers or workers, and adequate channels of information.

This competitive ideal, however, is a far cry from the actual employment practices of many large and powerful employers, with limited information about labor markets, constraints upon workers’ choices of employers, collusion of employers on working conditions, and so on. Such realities have invited unionization among workers, as well as government interventions in working conditions and worker-employer strife. As long as labor unions and national governments can strongly assert themselves for fair employment practices, we can expect that Market may pay in some proportion to each worker’s value-added. It is, however, quite doubtful that Market recognizes the incomparable complication of labor markets, due particularly to the inseparability of workers from both their services and their Culture. In view of the Market’s neglect of the natural environment [Hiwaki, 1998], among other things, we have reasons to doubt that the wages determined by the shortsighted Market account for the full costs in the long run, namely, the cost of acquiring Market-effective special skills and Culture- effective general skills, as well as the cost of sustaining the cultural stock and culture-related environment.

GLOBALIZATION AND EMPLOYMENT

An idealized competitive model of employment is usually credited to the neoclassical school of economics and can be traced back again to The Wealth of Nations written by Adam Smith. This book revolutionized the idea of economic development with the above-mentioned “invisible hand” and “self-interest”. The later application of these concepts in the course of the Industrial Revolution and of the imperialistic pursuit of power not only degraded the value of Culture but also set conditions convenient to the abstraction of labor from the underlying Culture for the sake of a short-run competitive model of employment. Moreover, the “invisible hand” (free and competitive market) has come to treat long-living and spiritually inclined workers much like material goods. Such treatment has seldom take heed of the known “peculiarities” of labor markets [Marshall, 1959]. The concept of “self-interest”, on the other hand, has helped reduce human motivation to a short-run individual self-interest and has encouraged a self- centered and aggressive character among workers. Together, they have made employment cut-and-dry and humanity grossly distorted over the long duration of time.

As an extension of individual “self-interest”, a national “self-interest” has excused the Western powers themselves to indulge in imperialism and neo-imperialism, to deprive non-Western peoples of their essential resources and, in doing so, spread the thought and lifestyle pertaining to such politicoeconomic concepts. It is no wonder that we often come across the well-worn argument for the competitive model of employment. Such an argument is allegedly based upon features common among modernized industrial countries, despite the existing differences, such as “size, climate, geographic characteristics, language, and cultural traditions, and form of government” [Reynolds, 1978]. The competitive model has been supported by many business organizations in the Western world and regarded by some adherents to the neoclassical school as an authentic model applicable across the world. Now that the global economy has become the leitmotif, the logic of global capitalism asserts itself under the wing of global corporations and financiers, reviving the crude law of the jungle to the detriment of Culture and humanity every-where.

Accustomed to their own convenient definitions of “self-interest”, such global entities, with their economic, financial and political influences unlimited by national boundaries and often augmented by their mother- country governments, have attempted to lord it over or impose their own rules on most societies in the world, neglecting the cultural and natural environments. Speaking of the far-reaching nature of the on-going globalization, William Greider put it: “The past is up-ended and new social values are created alongside the fabulous new wealth. ... Yet, masses of people are also tangibly deprived of their claims to self-sufficiency, the independent means of sustaining hearth and home. People and communities, even nations, find themselves losing control over their own destinies, ensnared by the revolutionary demands of consumers” [Greider, 1977]. George Soros declares, too: “It is market fundamentalism that has rendered the global capitalism unsound and unsustainable” [Soros, 1998].

The reviving law of the jungle under the guise of authentic and ideal Market has exerted drastically negative effects on the underlying Culture, regardless of rich and poor countries, shattering its already slighted values. This predicament of Culture, in turn, has affected the life of workers everywhere, as many global corporations and financiers together tries to change working conditions and even reshuffle workers throughout the world on some pretext or another, thereby replacing highly paid workers in the industrially advanced nations by way of the worldwide network of sophisticated computers, as well as by the exploitation of cheap labor in the developing nations. This tendency has necessitated a cut-throat competition among workers beyond their trades and beyond their national boundaries. This new competition has, in turn, accelerated an unprecedented confusion, anxiety and insecurity among workers, families and societies. This can result in public disorder, terrorism and even wars. To say nothing of such disasters, an utter neglect of Culture may entail a narrowing scope or, much worse, an impoverished state of Market itself in the long duration of time.

CULTURE-AND-MARKET VERSUS CULTURE-OR-MARKET

Culture and Market, respectively, are blessed with inherent dynamism of different kinds. To speak simplistic, the former tends to deepen and enrich itself over time, while the latter tends to broaden and strengthen itself over time. In other words, Culture tends to accumulate itself, while Market tends to expand its coverage. Such dynamic characteristics of Culture and Market, respectively, coincide with the ethos of Culture (long-term, cooperative, inward-looking and stock-oriented) and the ethos of Market (short- term, competitive, outward-looking and flow-oriented). If we can find the way to have Culture and Market interact properly, thereby respecting and augmenting each other, then all peoples, cultures and societies throughout the world may benefit enormously. However, if we let either Culture or Market stifle the other, all of us may lose drastically, since both Culture and Market constitute very important, and perhaps indispensable, bases of human heritage for the common good.

Today we are facing the very real danger of Market stifling Culture through the current onslaught of global capitalism or the escalated process of Market-driven globalization. If we simply look on as passive observers, Culture will most likely be trampled upon in all regions of the world, soon to a point which is beyond hope of recovery. This, however, may not be the end of the story, for such a doom on Culture will certainly visit Market, too, leading it to an unforeseen dead end. To explain this simplified surmise, we will take a diagrammatic approach to a possible relation between Culture and the competitive model of employment [Hiwaki, 1999].

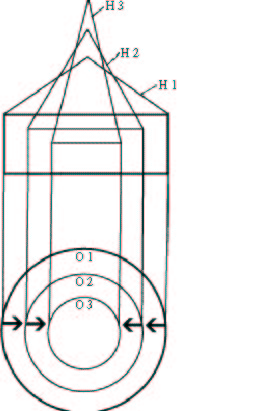

FIGURE 1 |

Now, in an initial long-term period, Market demand for labor services leads to forming an echelon of human capital (H1). For simplicity again, Market is assumed to pay only for Market-effective services. This means that Market ignores the indispensable support of Culture-effective services that are provided simultaneously by the same work-force. In other words, Market treats Culture-effective skills as free goods.

Such a rewarding scheme, of course, entails a serious consequence in the world where money speaks. The following generation of workers, sensing little contribution of Culture-effective skills to their prospec tive incomes, may become shy of learning such skills, thus reducing the cultural foundation over time. In the meantime, Market calls for new types of labor services. Accordingly, a second echelon of human capi tal (H2) is to be formed on the reduced foundation of Culture (O2). Such capital formation may at best relate only partially to the existing stock of human capital. Workers responding to Market demand are now amply rewarded, despite their possible weakness in cultural back- ground. Ignoring the cultural contents in labor services, then, Market further discourages future workers from learning Culture-effective skills, thus reducing the cultural foundation still further. Upon this ever-weakened foundation (O3), a third echelon of human capital (H3) must be formed in response to a change in Market demand, and it goes on, to the eventual complete obliteration of Culture. This also leads Market to a possible dead end.

In the above analysis, for the sake of simplicity we ignored that actual practices resembling the competitive employment might consider some cultural aspects of workers. It may be quite natural to do so, but it is done to a matter of degree. Normally, corporate managers tend to take short view of things and consider Market conditions first and foremost. Thus, even in an actual situation we can safely assume that sequences such as H1 to H2 and H2 to H3 tend to be uneven and largely disconnected from one another. In our simplified illustration, each different generation of workers responds in its own way to each Market shift. Also, the average worker becomes further and further detached from Culture in this sequence. This may, in turn, imply that Market faces a growing difficulty in its own expansion.

Under the above setting, newly demanded skills of increasing sophistication will most likely be mastered by a decreasing proportion of people, thus accelerating both socioeconomic polarization and politicoeconomic animosity. Also, over time people in general tend to lose sophisticated command of language (an important element of Culture), when the growing specialization of skills may require more intricate and effective communication between the specialized and the non-specialized. Further, they tend to lose a cultural catalysis in their inter-personal relations amid the growing realities of cut- throat competition and an increasingly cut-and-dry style of life. Moreover, people tend to lose their culturally-nurtured sense of responsibility and public order in the midst of an explosive freedom generated by free and competitive Market. A point is reached at which more and more businesses have to operate on a more shaky cultural ground, facing increasingly uneasy, self-centered, capricious or infantile workers and consumers. Reliability and trust tend to dissipate rapidly, resulting in a societal collapse and a fatal predicament of Market.

Alternatively, we can at least in theory choose a more appropriate model, namely, Culture-enhancing employment that empowers Culture and Market simultaneously. Our theoretical model encourages a harmonious and synergistic interaction between Culture and Market with two basic principles. A first principle asserts that Market must account for both Market-effective and Culture-effective skills. In other words, Market must pay for both equitably and sufficiently. Payment only or mostly for Market-effective skills, for instance, grossly distorts the formation and allocation of skills, simply encouraging only the skills which are purely Market-effective. A second principle asserts that all individuals, all firms and all levels of government must strive for the continuity and enhancement of both Culture-effective and Market-effective skills to have both the skills accumulate steadily over time. Such endeavors may rein-force the cultural foundation and augment the abilities of individuals, peoples and societies in a rapidly changing world.

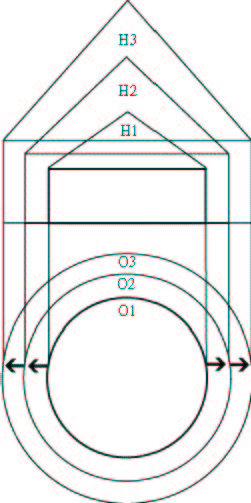

Now, we will contrast our Culture-enriching approach to employment with the competitive employment model, beginning again with a reasonably rich cultural foundation (O1) in Fig. 2. An introduction of Market encourages an echelon of human capital (HI) to be formed according to Market demand. Equitable and sufficient payments for both Culture-effective and Market-effective skills facilitate a synergistic interaction between these skills to enrich the cultural foundation over time, contributing simultaneously to a well- balanced sophistication of the people. Upon this richer foundation (O2) a second echelon of human capital (H2) is to be formed in response to a change in Market demand. Appropriate payments, again, enrich the cultural foundation further.

FIGURE 2 |

CONCLUDING REMARKS

In the world of cultural diversity, accounting for Culture-effective skills, together with Market-effective ones, are crucially important for human and socioeconomic development. Exposing the core idea of a Culture-enriching approach to employment in the above, I am well aware of the formidable nature of our challenge. Given the ever-stronger thrust of Market with the accumulated momentum of globalization, a short-run Market emphasis in employment may prevail throughout the world. I am FIGURE 2 quite apprehensive of such a dreadful consequence, particularly because self-centered global corporations and financiers have been practically turned loose to spread a profit-motivated Market fundamentalism in the world economy. The crudest imaginable Market may be well on the way to dig its own grave by trampling down Culture and thereby for-ever depriving all of us the opportunity to enhance our thought frame and lifestyles. While at the same time, we may forever lose our opportunity to generate a culture of peace in the global community.

Thus, our argument is straightforward. As a step to rectify the prevailing bias toward Market, a Culture-enhancing employment is indispensable. Such employment can promote a culture of peace and offer a much greater scope than otherwise exists for individual skills, activities, enjoyments, achievements, identities and lifestyles, as well as for health, comfort and independence. A Culture-enhancing employment may also provide us with a far greater chance for equitable distribution of income and sustainable development. I am of the opinion that Market can be cultured to have both long-term and cultural emphases. Put differently, the shortsighted Market reflects nothing but our shortsighted thinking, attitude and behavior. This tendency of vicious circle can be rectified, if we so will, by our resolute endeavors to cultivate and accumulate an ever-greater dimension in our time-and-space thought frame. For such an expanding thought frame, in turn, changes our value system, lifestyles and socioeconomic activities. Then, the idea of adapting ourselves to a Culture-enhancing employment may not be far- fetched after all. Such a practice of employment may not only harmonize Culture and Market for their mutual improvements but also conduce to a balanced human development and a culture of peace, as well as to sustainable development.

The recent terrorism against the American economic and financial centers, as well as against her political and military nerve, has a strong impact upon the thinking of market-driven globalization and the market-centered approach to employment. There are, perhaps, many deep-seated causes for such horrible and grievous acts of terrorism, and we must be highly cautious in our search for the causes and we must avoid arriving at simplistic conclusions or equally simplistic counter-measures. One truth, however, is very clear: such a self-destructing act of terrorism does not simply appear without reason. It can only be the last resort of the persons directly involved, aside from those who manipulate them for political reasons or others. Such an act may be due to black despair, probably having deep roots in an environment of extreme impoverishment, a total deprivation of human dignity or an intense hatred and anger toward the aggressor of life, faith, identity and independence.

The market-driven globalization can be considered as one important culprit causing such despair. For it caters to the logic of the strong, as well as to the logic of the Modern West. This globalization, on the one hand, has no doubt increased the volume of world production and trade, and, on the other hand, has given rise to billions of starving, deprived, despairing and angry people alongside the relatively small minori ty of superbly favored, rich and prodigal people, as well as to cultural and environmental devastation. In addition, the market-driven globalization has been accompanied by a market- centered practice of employment, which, in its eagerness to emphasize competition and efficiency, has largely emancipated acquisitive and aggressive spirits for the win-or-lose competition, on the one hand, and has dehumanized the otherwise culture-worthy and culture-intensive productive activities, on the other hand.

REFERENCES

Greider, William (1997); One World, Ready or Not, Simon &

Schuster.

Hiwaki, Kensei (1998); Sustainable Development: Framework for a General

Theory, Human Systems

Management, Vol. 17, No. 4.

Hiwaki, Kensei (1999); Culture of Peace and Long-run Theory of

Employment, G. E. Lasker and V.

Lomeiko (Ed.) Culture of Peace: Survival Strategy and Action Program for

the Third Millennium, The

International Institute for Advanced Studies in Systems Research and

Cybernetics (in cooperation with

UNESCO)

Marshall, Alfred (1959); Principles of Economics, Macmillan.

Raynolds, Lloyd G. (1978); Labor Economics and Labor Relations,

Prentice-Hall.

Smith, Adam (1937); The Wealth of Nations, The Modern Library.

Soros, George (1998); The Crisis of Global Capitalism, Public Affairs.

Dr. Kensei Hiwaki is Professor Economics at Tokyo International University, and also serves as a Member of the Editorial Advisory Board of both the BWW Society and Bibliotheque: World Wide. In conjunction with his participation with the BWW Society, Professor Hiwaki is Founder and Chairman of the Committee for Cultural Enrichment and Diversity.

Professor Hiwaki has put forth academic economic theories documenting that Market Forces and Cultural Enrichment can work together, not only to their mutual benefit, but to the lasting benefit of developed and underdeveloped nations and highly varied cultures throughout the world.

[ BWW Society Home Page ]

© 2002 The BWW Society/The Institute for the Advancement of Positive Global Solutions