|

Page One Featured Paper: Neuropsychiatry:

The System of Narcissism:

Five Ontological Locations of Self-Observation and Operating Principles

by Dr. Bernhard Mitterauer Professor Emeritus, University of Salzburg Director, Volitronics-Institute for Basic Research Wals, Austria

Link for Citation Purposes: https://bwwsociety.org/journal/archive/the-system-of-narcissism.htm |

Abstract

From a systemic point of view, the psychological concept of narcissism is interpreted as organismic self-reference or self-observation. On the basis of Guenther’s polyontological theory of subjective systems five ontological locations of self-observation are defined representing elementary capabilities of a self-conscious living organism respectively our brain. These hardware, cognitive, temporal, actional and boundary-setting capabilities of self-observation are outlined in a self-referential system. The interaction between the locations of self-observation has to cope with dialectical concepts, since not only a holistic operating principle is at work, but a discontextural (no logical relations between the topic areas) and a complimentary one as well. The model proposed should be of particular interest for the study of psychopathological phenomena such as depression, mania, and schizophrenia that can be deduced from disorders of the distinct capabilities of self-observation.

1. Introduction

The myth of Narcissus, a self-loving youth, as described by Ovid (1983) in the Metamorphoses has repeatedly challenged deeper interpretations (Freud 1914). In the second half of the last century, schools of depth psychology in particular have grappled with the concept of narcissism. Narcissism was interpreted on the one hand as a fundamental principle of life (Pulver 1970), and on the other hand as an elementary psychopathological phenomenon (Kernberg 1975). In psychiatry, one speaks of narcissistic personality disorders, which are characterized by increased self-centerdness (Yakeley 2018).

In an interdisciplinary basic study we used the concept of narcissism as a synonym for organismic self-reference. Accordingly, narcissism includes those principles of self-reference that guarantee the preservation of the circular organization of living systems and their identity (Pritz, Mitterauer 1977). In addition to von Foerster (1993) and other cyberneticists (Varela 1974), Guenther (1967a) made a fundamental contribution to the formal representation of self-reference. In the following, I will outline the system of narcissism as a model of polyontological (from Greek: poly = many; and ontological loci) self-observation.

2. The Five Ontological Locations of Self-Observation

Gotthard Guenther’s transclassic logic actually describes a polyontological reality which is particularly suitable for the formal interpretation of the individuality of living systems (Mitterauer 1998, 2010, 2014). In the study “Time, timeless logic and self-referential systems” Guenther developed a polyontological system by introducing new ontological locations that go beyond a three-valued understanding of reality. The following question arises:

“What do these new ontological loci signify? The shortest possible answer is: Being, its reflection in thought and time represents the whole range of objective existence as reflected in three-valued ontology. Yet there must be a subject of cognizance conscious of an objective world. This subject must be capable of distinguishing between the world as outlined, in its ontology, its thought-image of this world, and itself as being the producer of the image. Since the first three loci refer to the world, the fourth locus must accommodate the image making and the fifth the producer of it.” Guenther further emphasizes that the concept of thought or thinking is ambiguous: The classic tradition of formal logic neglects this ambiguity. And does not understand the Janus-face of subjective self-reference… Subjectivity is both the still image of the world as well as the live process of making an image; and what we call a personal ego constitutes itself in the triadic relation between environment, image and image-making.” I am quoting Guenther in such detail because I would now like to attempt to outline a model of self-observation on the basis of polyontology.

When speaking of self-reference or self-observation, it is first necessary to take a position on the concept of the self. This concept is often used, but an exact definition of it is usually lacking and is also very difficult. One operational way of describing the concept of the self is to equate the role of the living observer with that of the personal self (Mitterauer, Pritz 1978). One can make the following proposition: the self is a self-referential (closed) living system with the ability to observe itself. Or: whenever it is a matter of systems of a self-observer, self-reference can be interpreted as self-observation. If we assume that our brain has numerous subsystems with the ability to observe itself, these systems can be seen as sites of self-observation. In neurobiology, one speaks of “many selves systems”, which could be located in certain areas of the brain (Baars 2023; Betka et al. 2022). I would now like to try to show that the five ontological locations that Guenther considers to be constitutive of a subjective system like us humans can not only be interpreted as elementary sites of self-observation, but above all embody the basic capabilities that a human brain needs in order to be viable and to maintain its identity.

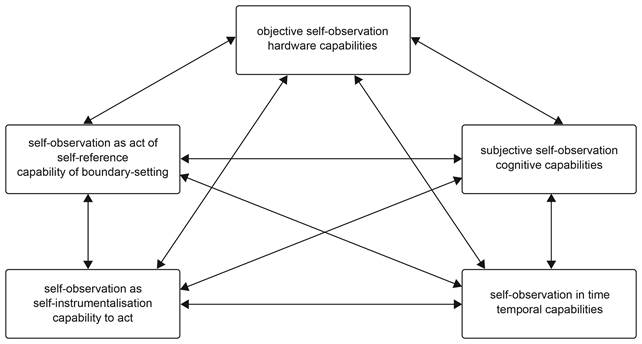

Figure 1. Model of the five ontological locations of self-observation (see text)

In Figure 1 the five locations of self-observation are shown as a closed (self-referential) system. In relation to the brain, “being” is comparable to objective self-observation. This is about the hardware capabilities of the brain. “The reflection of being in thoughts” can be interpreted as subjective self-observation or self-representation. This is about the brain's ability to think. Both objective and subjective self-observation take place in time. In what time? (This will be discussed further below). The fourth ontological location that Guenther assigns to a subject is a location of self-observation as self-instrumentalization. Self-instrumentalization means the ability to act through the self-production of tools. In other words: the genome produces organs such as the brain to implement its programs in the inner and outer world. This is also the essence of self-organization. A self-organizing system is capable of instrumentalizing itself with “tools” (Greek: organon means tool). Finally, the fifth ontological location which as an act of self-reference defines and guarantees the ego or the personal self, can be directly adopted as a location for self-observation. This location for self-observation has the existential ability to set boundaries.

As already mentioned, self-observation occurs in time. If one examines the time problem based on the polyontological model of self-observation, one can first establish that objective self-observation in the sense of our genome operates in both ontogenetic and evolutionary time sequences. Given that in ontogenesis the end conditions are already determined by the initial conditions, then programmed cell death (apoptosis) is a typical example. Basically, the structure and function of the brain enables creative self-observation by thinking up new things. In addition, if a person is able to implement these new ideas themselves, he (she) has taken an evolutionary step. Note, the evolutionary concept of time does have initial conditions, but these do not determine the end result so that evolution is open to the future (Guenther 1967b) and generates a creative space. Therefore, objective, subjective and self-instrumentalizing self-observation are in an interplay between ontogenesis and evolution.

But which concept of time is self-observation subject to as an act of self-reference? Here a third concept of time is required, which can be characterized as permanence (Mitterauer 1989). Permanence seems to be paradoxical because it is “atemporal”, i.e. not immediately subject to time. Permanence is, however, the time conception in which the act of self-reference run. Of significance, it does justice to the fact that every circular living organization obeys a structural and functional principle. Only the structures are changeable, not the function of self-reference. This is the fundamental principle of narcissism. We are capable of constantly changing ourselves structurally and making suitable tools for a new world. We only have these capabilities because the act of self-reference, independent of the inner and outer world, maintains the functions of self-organization.

3. The Operating Principles of Narcissistic Self-Organization

As already stated above, the model of polyontological self-observation represents a closed system that potentially operates permanently through the act of self-reference. Without going into the myth of Narcissus in more detail, it is evident that the young man is caught up in self-loving self-observation and an insatiable longing for permanence. If one assumes that self-reference or narcissism is a fundamental principle of the living systems, especially humans, then it seems obvious that this is a purely holistic function which, however, produces paradoxes. Decisively, if we base the model of self-reference on the polyontological theory proposed, then self-reference shows dialectic, whereby essentially three operation principles can be described:

If we consider again the locations of self-observation shown in Figure 1, they not only represent independent locations, but also each embody an independent topic area. Therefore, in the operations of self-reference, both polyontology and polythematics are involved. Our model of self-reference or self-observation does indeed capture the general topic of the brain’s capabilities, but the individual topic areas are not logically related from the outset. For example, there are hardware functions in the brain stem reticular formation that have no logical relation to cognitive functions in the prefrontal cortex. Guenther (1971,1973) speaks of discontexturality. However, even if there is no logical relation between the individual locations of self-observation, they are nevertheless “held together” by the act of self-reference. “ The living organism… is a cluster of relatively discontextural subsystems held together by a mysterious function called self-reference and hetero-referentially linked to an environment of even greater discontexturality” (Guenther 1971).

Basically, the simultaneity of holism and discontexturality requires a dialectical theory of self-reference or self-observation, whereby the following three operating principles can be described:

1. The holistic operating principle: this is about the permanent safeguarding of the elementary functions of the whole system.

2. The discontextural operating principle: the safeguarding of the elementary functions takes place completely separate from the topic of self-instumentalization in the inner and outer world. Guenther (1976a) speaks of “detachment of the subject from the environment as well as from its own thoughts.”

3. The complementary operating principle: although the holistic and discontextural operating principles function antithetically, this dialectical problem is solved “integratively” through the act of self-reference. Therefore, the function of self-reference is both boundary-setting and integrative.

4. Concluding Remarks

The polyontological model of self-observation and its interpretation as a life-guaranteeing principle of narcissism represents an attempt to make Gotthard Guenther’s theory of subjective systems fruitful for interdisciplinary research (Mitterauer 2021).

This model should be of particular interest for the study of psychopathological phenomena such as depression (Mitterauer 2009, 2016), mania (Mitterauer 2020a), schizophrenia (Mitterauer 2020b) and “sufferings of the will” (Mitterauer 2020c) that can be deduced from disorders of the distinct abilities embodying the five sites of self-observation.

Acknowledgment

I am very grateful to Marie Motil for preparing the final version of the study and to Christian Streili for designing the figures.

References

Baars BJ. (2003) Brain, conscious experience and the observing self. Trends Neurosci. 26:671-5.doi:10.1016/j.tins.2003.09.015

Betka S., Haemmerli J., Park HD. et al. (2022) The brain mechanisms of self-identification and self-location in neurosurgical patients using virtual reality and lesion network mapping. medRxiv preprintdoi:https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.22.22272566

Freud S. (1914) Zur Einführung des Narzißmus. GWX, 137-170. Fischer, Frankfurt

Guenther G. (1967a) Time, timeless logic and self-referential systems. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci 132,396-406.

Guenther G. (1967b) Logik, Zeit, Emanation und Evolution, Westdeutscher Verlag, Köln

Guenther G. (1971) Natural numbers in trans-classic systems. Journal of Cybernetics 1, 50-62.

Guenther G. (1973) Life as polycontexturality. In: Wirklichkeit und Reflexion, Fahrenbach H. (Hg.) Neske, Pfullingen, 187-210

Kernberg OF. (1975) Zur Behandlung narzisstischer Persönlichkeitsstörungen. Psyche 29, 890-905.

Mitterauer B. (1989) Architektonik. Entwurf einer Metaphysik der Machbarkeit. Brandstätter, Vienna

Mitterauer B. (1998) An interdisciplinary approach towards a theory of consciousness. Bio Systems 45, 99-121.

Mitterauer BJ. (2009) Narziss und Echo. Ein psychobiologisches Modell der Depression. Springer, Vienna

Mitterauer BJ. (2010) Many realities: outline of a brain philosophy based on glial-neuronal interactions. Journal of Intelligent Systems 19, 337-362.

Mitterauer BJ. (2014) Polyontologie. Architektonische Philosophie des Gehirns, Beitrag II, Paracelsus, Salzburg

Mitterauer B. (2016) Hyperintentionality hypothesis of major depression. Disordered emotional and cognitive self-observation in tripartite synapses and the glial networks. International Journal of Brain disorders and treatment 2: 015

Mitterauer B. (2020a) The passion of will in mania: towards a philosophy of mental disorders. The Bi-Monthly Journal of the BWW Society 20, 1-10, https://bwwsociety.org/journal/current(2020/jan-feb/the-passion-of-will-in-mental-disorders. htm

Mitterauer B. (2020b) The passion of will in schizophrenia: towards a philosophy of mental disorders. The Bi-Monthly Journal of the BWW Society 20, 31-40, http://bwwsociety.org/journal/current/2020/jul-aug/the-passion-of-will-in-schizophrenia.htm

Mitterauer B. (2020c) Psychobiological model of volition - implications for mental disorders. Open Journal of Medical Psychology 9, 50-69

Mitterauer BJ. (2021) Outline of a brain model for self-observing agents. Journal of Artificial Intelligence and Consciousness 8, 171-182.

Mitterauer B., Pritz WF. (1978) The concept of the self: a theory of self-observation. Int.Rev.Psycho-Anal. 4, 179-188.

Ovidius Naso (1983) Metamorphosen. Artemis, München

Pritz WF., Mitterauer B. (1977) The concept of narcissism and organismic self-reference. Int.Rev. Psycho-Anal. 4, 181.196.

Pulver SE. (1970) Narcissism: the term and the concept. J. Am psychoanal. Ass. 18, 319-341.

Varela, FJ. (1975) A calculus of self-reference. Int.J. General Systems 2, 5-24.

Von Foerster H. (1993) Wissen und Gewissen. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt

Yakeley J. (2018) Current Understanding of narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder. BJ Psych Advances 24, 305-315.