|

Abstract:

Human Resources decision making has taken on a meaningful role in the core of organizations’ development and delivery of services. This paper deals with the challenges of decision making in a Human Resources Manager’s function. Decision making within this function is particularly challenging in that it requires both a consistent, equitable approach to ensure fairness, policy and compliance as well as an individualized approach considering psychological and emotional safety in order to ensure thoughtful care for each unique situation. While this balance is a growing capability of Human Resources leaders, there has not yet been a formalized approach that acknowledges this unusual level of nearly infinite complexity. This paper discusses the challenges of balancing the unique, bifurcated needs of human-centered decision-making, in particular taking into account the enhanced need for emotional intelligence in Human Resources decisions by means of providing our survey results conducted across Germany. A new model and framework are being presented, which can support Human Resources professionals in multiple organization types to understand tradeoffs and to minimize risks by bringing sharper decision making to individual, team and hierarchical decisions while deepening consideration of organizational structure and context. This innovative model ensures that six critical aspects of decision making are thoroughly analyzed in order to make the most meaningful and impactful decisions. As a result, leverage of intentional Human Resources decision making tools will most probably enhance satisfaction, trust and productivity and will stimulate the success of an enterprise.

Keywords: human resources, management, decision making, emotional intelligence, collaboration.

I. Introduction

The function of Human Resources (HR) has become increasingly strategic over the last decade as the shifting landscape of artificial and human intelligence impacts the type of work that people are doing and the resulting needs from the organizations to care for and develop the skills those of the people involved.

What was once a highly transactional feature has evolved into one that is at the core of most business priorities and often Human Resources business partners become the right hand of the CEO and own Business Leadership. With this it has come a parallel shift in the internal mindset and time and resource distribution within Human Resources functions. More systems form the backbone of what was once manual process and more active professional leadership and skill-based development along with employee satisfaction and engagement have become the focus of many HR leaders and managers.

Many authors have noted the importance of HR practices, once institutionalized, are notoriously intractable are the highest asset for the overall success of the whole company. The challenge here is to implement a consistent existing set of interconnected processes in a continuous entanglement across all the HR structures both within large and small organizations. In this respect, an insightful coordination of communication, training, incentive and information technology systems across the firm are required, for it is the redundancy of mutually reinforcing HR practices that ultimately underlie the impact of HR systems on organizational performance (Wright, Paauwe & Guest, 2012).

According to P. Buhler (2002) human resources are the people (including their knowledge, skills, potential, and abilities) within an organization who perform the actual work of the organization for attaining the success of the whole company at large. According to the author, the efforts of the people involved in the process of labor enables the entire organization to meet its objectives. This brings us to the belief that human resources are very important within any organization at hand, which together ensure the actual success of the latter.

While a significant evolution has taken place in the function of Human Resources sector, the decision-making processes in the very same function have not been made as sophisticated an evolution as desired. The decision-making mindset for many remains too often based on historical knowledge, and decisions are made either based on intuition or thick data but rather on big data collection, but not with the level of intentionality, consistency and clarity as other functional business decisions that may have made specific changes, analytical requirements, or even legal guidelines.

E. Lawler and J.W. Bourdreau (2009) state that currently apparently organizations are creating new strategic initiatives and significantly changing how they operate. They are utilizing new technologies, changing their structures, redesigning work, recruiting new talents with soft skills, relocating their workforces, and improving work processes to respond to an increasingly demanding and global competitive environment. According to the aforementioned authors, distribution of duties amongst the employees, employers and the board of trustees is one of the most important issues in today’s modern institutionalized world, where human capital is of utmost importance.

In this paper, we discuss not only the challenges with the status quo but the specific impact on Human Resources functions and leaders. Considering the vast array of decisions in the human resources space, from high touch interpersonal decisions such as individual compensation or interpersonal issue resolution to large-scale decisions such as performance management systems design and personnel integration in an acquisition, there is a clear need for increased clarity and rigor in decision making within the HR function. Further to the decision types that need to be made, the consideration of psychological safety and emotion management and emotional capability in such decisions is truly critical.

It goes without saying that each decision, no matter the depth or speed of decision making, should have a significant depth of consistency and rigor applied and in order to do that, should additionally consider multiple critical factors. Consideration of these factors, whether in an extensive analytical and data-based way or whether in an intuitive and emotional way, can add consistency, objectivity and generate new innovative ideas and perspectives within the course of a decision-making process. Specific questions and approaches to each of the six factors can lead to a mapping of possibilities for a decision or leadership committee to quickly evaluate and better understand.

Human Resources, depending upon the organizational construct, covers a vast array of disciplines such as recruiting, learning, organizational design and development, employee relations, employee satisfaction, metrics and analytics, compensation, benefits and even more. As these functions are increasingly professionalized and even becoming credentialed in many cases, and as the employment environment becomes even more competitive, the need for a thoughtful framework around the decisions that impact so many lives has become even more pressing.

Additionally, it is essential to note that emotional intelligence (EQ) holds an irreplaceable importance here as the presence of authentic psychological safety is essential which ensures that human-centered decisions are made in an impactful manner. The models presented below challenges traditional assumptions that have HR professionals relying on historical and intuitive data and moves toward a sharpened focus on key aspects of HR that are helpful in building and maintaining empowering and exciting work environments for individuals, teams and leaders.

II. Decision Making Definition & Challenges

Individuals, teams and leaders within organizations make dozens of decisions each day. These decisions may be small or large scale and many challenges, even those unseen, may arise from variability and weakness in this process. The key challenges and different types of decisions are discussed below.

According to Plaut (2008), decision making is larger than problem solving but it is one portion of the process of problem solving, selecting a solution after considering the causes of the problem and the universe of solutions. According to the author, individual, team-based and hierarchical decision making, often seen as differential modes of decision making, have qualitative commonalities and conditions that frequently exist in strong decision-making processes. When strong decisions are made with group consensus and engaged, empowered individuals, there is buy-in and a corresponding reduction in barriers to implementation.

Yet, it is well known that strong decision making is a challenge in many organizations and can derail or change entirely the course of progress for a company. Research shows that only 20% of organizations say that they excel at decision making and that the cost of ineffective decision making is 530K hours in lost time and $20mm in wasted labor cost (Decision Making in the Age of Urgency, 2021, online).

Different decision types layer even more complexity as illustrated by the ABCDs of categorizing decisions based on McKinsey research (de Smet et al., 2021, online) in Exhibit A, which illustrates the mostly frequently applied decision making types, namely a) big bet decisions, b) cross cutting decisions, c) ad hoc decisions, d) delegated decisions, and the level of their frequency.

The illustration of the Exhibit A below well depicts the main types of decisions made alongside the explanations of their nature and essence used within each and every organization.

Exhibit A: The ABCDs of categorizing decisions (de Smet et al., 2021, online)

With so many decision types and stakeholders, it is logical that decision making has been described as a tension (Transcending Either-Or Decision Making, 2020). In fact, tension exists in decision making in both the prospect that there may be no way to please every stakeholder and in that there may be tradeoffs that create precedents or downstream impact. Making tradeoffs and reaching consensus is particularly critical to the resolution of tension which is decision making and the core of that capability revolves around the identification of root causes and the building of consensus with stakeholders around decision alternatives. Identifying the root causes of a problem begins to ensure that decision alternatives address all sources of tension. Teams who make decisions together by exploring the detailed differences between options, understanding the full spectrum of opinions by hearing every team member regardless of hierarchy, and moving through disagreements in a constructive and collegial way could be described as high-performance decision-making teams.

In this connection it can be noted that this kind of common pitfall happens when topical experts are excluded from problem solving and decision-making processes. Without the broader benefit of various types of knowledge and experience, a lack of humility, a difference in action orientation, cultural bias, and hierarchy can stunt effective, agile and informed decision making.

According to recent research (Mallon, 2020), a critical step in resolving some of these issues and complexities lies in clarifying decision rights. Clarity in decision rights is indeed a hallmark of mature organizational models. These mature organizations demonstrate a number of commonalities: who is empowered to make decisions, clarity on what decisions need to be made at which levels and lastly clear operating processes and tools for decision making.

Additional research by Hill, Tedards et al (2021) discusses the need for decision making innovation beyond standard techniques that many have integrated into existing organizations. Agile or lean operations for example, are often used as processes and approaches to accelerate problem solving and decision making.

However, Hill and Tedards (2021) point out to the fact that these processes are not enough. The inability of organizations to make fast decisions is often the culprit in creating roadblocks and barriers to the truly creative and collaborative problem solving that could make real change happen in an organization. The authors further suggest, after decades of research that “including diverse perspectives, clarifying decision rights, matching the cadence of decision-making to the pace of learning, and encouraging candid, healthy conflict in service of a better experience for the end customer” (2021, online) are true enhancements to decision making and can help unleash innovation.

The remedy for this set of challenges in decision making may seem clear - clear decision rights, expert engagement, diverse perspectives… but in practice are complex in their execution. Such solutions can build complexity rather than speed and are therefore antithetical to the fast pace of many organizations. In research from de Smet et al. (2021) the concept of employee empowerment is central to making strong decisions. The concept simply stated is that the empowered employees make good decisions and resolve problems collaboratively minimizing the risk of insolvency. The minimization of micromanaging and a stronger tendency toward inspiring leadership and empowerment of true experts through episodic engagement may indeed hold one of the keys to collaboration and buy-in.

A case study about Apple (Podolny, Hansen, 2021) illuminates the importance of organization design in decision making as the design of an agile organization optimizes for the leverage of expert knowledge as well as innovation and appropriate risk flagging and mitigation in decision making. Apple’s key to innovative success is not just the organization design itself but also the depth of expertise and trust in those organizational components to problem solve and make decisions independently. Here after the re-structuring of the company by Steve Jobs experts are leading expert, where everybody is involved in the field of their proper expertise.

Anti-bias and noise minimization are additionally critical for consideration when evaluating decision making effectiveness. In his research, E. Tippet (2019) discusses creative ways to mitigate bias in particular within decision making processes. While many suggestions are important and relevant, the concept of “revealing hidden decision makers” speaks to many of the above challenges - from decision rights to expertise to the impact of organizational structure. In order to minimize bias and the related type of noise that is discussed by D. Kahneman in his podcast and book about Noise (2021), truly rethinking the approach to and design of organizations and expertise-based roles in decision making should be at the top of a CEO agenda.

Lastly, one final concept ties all of these seemingly non-related decision-making models and criteria together is the concept of psychological empowerment and psychological safety. This concept has been elaborated by C. Schermuly, who states “Within New Work we have flat hierarchies, which have to take into account the motivation, aspirations and desires of the co-workers and consider a psychological approach” (2021, online). Indeed, this work reflects on the importance of psychological empowerment and safety which is endemic to all of the previously discussed criteria for excellence in decision making: clarity of decision rights, lack of bias, diversity of perspective, collaboration, expertise, empowerment and organizational optimization.

III. Decision Types in Human Resources Functions

Decision making appears on its surface to be a simple and daily, sometimes even automatic human process. However, as demonstrated by the richness of literature and concepts around this topic, the multilayered complexity of decision making may well be the differentiating factor between a good and an excellent leader and good versus excellent business outcomes. Within the realm of Human Resources, this skill is especially poignant because of the variety of decision-making roles that Human Resources professionals play as well as the variety of archetypes of decisions that HR professionals are responsible for managing.

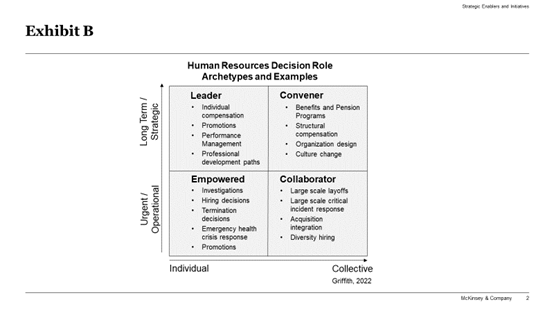

Because of this wide scope of responsibility, there is a broad variety of decisions - data, intuition, experience, etc. that an HR usually should rely on based on big data and thick data. The model proposed in Exhibit B illustrates this vast array of decisions and organizes them into four key problem-solving modes.

Exhibit B: HR Decision Roles, Archetypes and Examples

The decision types specific to HR exist in two dimensions, individual vs. collective and urgent/operational vs. long-term/strategic. Individual decisions are those that impact one human being at a time. A specific promotion, a change in compensation, a career path, a performance review, a harassment case, an abuse, and/or a health issue are examples of individual decisions that may arise. These are considered individual because while they may impact the larger organization, the impact on the individual is most profound and should be considered above all. By contrast, collective decisions are those that primarily impact the broader organization. Benefits programs, pensions, compensation philosophies, large scale decisions such as acquisition integration or workforce strategy are all examples of collective decisions.

The second dimension of HR decision making is related to time which is not always but very often associated with the operational, operational short-term topics versus strategic longer-term topics. Short-term topics may be those that require immediate or rapid decision making, writing a severance agreement to separate with an employee, promoting an employee, hiring a new employee or reacting to a counter offer from an existing employee. Longer term topics are those that both take longer to consider but also have longer term implications. Execution plans, large scale cultural change, transformations of organizations structure may be examples of longer-term topics. Longer term topics follow the arc of the strategic direction of the company - to attract the best talent would have a different compensation strategy than to hire multiple lower level employees, for example.

When put together, these dimensions of individual vs. collective and short-term vs long- term create four unique decision archetypes that Human Resources Professionals should take into consideration.

The four types describe the HR role in the decision and are: a) empowered, b) collaborator, c) convener and d) leader. These four types are defined and explained below (source: McKinsey & Company, 2022).

Empowered: Urgent operational decisions that need to be made with regard to an individual person are decisions that Human Resources leaders should be empowered to make with autonomy. These may be topics such as dismissal for harassment, eligibility for a surgical procedure, granting of bereavement days, small compensation adjustments or payroll advances. These most often may be personal and confidential matters and therefore it makes sense that the HR leader would be empowered to make such a decision.

Collaborator: For decisions that are urgent and still operational in nature but have a larger collective implication rather than an individual only implication, the Human Resources leader should operate as a collaborator in decision making. This collaboration may be simply with another HR expert but is more likely with someone in a separate function such as Finance or an operational business leader. These decisions are larger in scope and integrate multiple people and business units. For example, a response to a large-scale industrial accident with multiple injuries or a governmental shift in regulations effective immediately that radically changes operations. The complexity level of these decisions will be high and the Human Resources leader should have an important seat at the table along with the other relevant stakeholders.

Leader: In some instances, there are decisions that will impact an individual in the longer term. Examples of these situations may be around a difficult performance management discussion, a decision to change compensation structures, titles or roles. In these cases, the HR leader’s role is that of exactly their title, a leader. A common fallacy, acting as a leader does not mean acting alone or with full individual autonomy. Acting as a leader in this model means assessing the situation, understanding and engaging any relevant stakeholders and making a final and informed decision which is shared with all relevant stakeholders.

There are many different ways of leading people and accordingly there are also accordingly different leadership styles: a) autocratic, who are the authoritarian leaders, b) charismatic, who have the charisma to enchant and inspire the followers, c) transformational, who leads the groups in transforming the reality for the better, d) laissez-faire (otherwise known as delegative), when the leaders let the co-workers and followers a high autonomy on having things done by means of providing them the appropriate tools, e) servant leaders, where the followers are always supported by the leaders, who is always there for help and “serves” them to excel in their skills. This type of leadership was first proposed by Robert Greenleaf, f) transactional leadership, where the people involved know their roles and responsibilities, g) supportive leadership, where the people involved are assigned task, but also provided tools to complete them, h) democratic leadership (otherwise known as participative), where all the people are involved in decision making and operating (see Kippenberger, 2002; Kumari & Singh, 2019).

In fact, no matter the leadership style, the leader-based HR decision archetype is critical for longer term decisions impacting an individual.

Convener: Decisions that will have more lengthy implementation timelines and will impact multiple stakeholders are those in which Human Resources should play a convener role. The role of Human Resources is likely to be incredibly central in particular where the topic is people related. For example, a long-term strategy around pensions and retirement plans or a total rewards strategy would require the HR leader as the lead convener but also the input of operational and financial leadership because of the far-reaching impact of the decisions. Many organizations have made significant decisions in the past years around retiree benefits, for example. While this is tactically a part of the Human Resources work, the strongest leaders will convene a group of diverse stakeholders to engage in a discussion about implication and implementation. Many times, an external expert is engaged in leading the decisions. Convening this group whether it includes external experts or not is the responsibility of the HR leader in these types of decisions in addition to bringing analysis, data, experience and an informed perspective to the decision table.

IV. Challenges in Decision Making for Human Resources Leaders

Covered in the first section of this paper are a set of clear challenges to general decision making. These challenges include the following six factors:

1. Multiple stakeholders are not properly engaged or engaged at all;

2. Root causes of problems are not properly identified;

3. Expertise and diverse perspectives are not engaged;

4. Excessive hierarchy leading to limited empowerment;

5. Lack of clarity of decision rights leading to slow or non-existent decisions;

6. Lack of psychological safety in risk taking and fear of incorrect decision making.

Each of these six challenges are present of course in Human Resources decision making, however, some challenges are amplified and some additional considerations exist as well. While 40% of top performing companies may base decisions on intuition (Roth, 2021), in Human Resources, most decisions must be more data and fact-driven. From the outside many consider Human Resources to be the softer side of a corporation and while empathy and caring is critical to effectiveness, compliance and risk management are equally if not, in some cases, more critical. In order to meet the challenge of more fact-based Human Resources decisions, ⅓ of HR leaders have adopted Artificial Intelligence to assist in decision making (Dearborn and Swanson, 2017, p.18).

This increased focus on the importance of people in an organization has been a hallmark of the move over the last decades from a function that was entirely operational to a highly strategic part of an organization. Thence, we can come to think that a strategic Human Resources Management has become critical and requires complex problem solving, program design and high-level decision making. This high-level decision making is represented in the four archetypes in Exhibit B.

In order to operationalize these four archetypes of decision making in an environment of Strategic Human Resources requires focus not only on the six factors listed above but with specifically amplified focus on engagement of appropriate stakeholders, expert perspectives and clear decision rights. In addition to these six factors, risk-mindedness and cognitive bias are critical additional considerations, where people are governed by their prejudices or cultural constraints and individual beliefs.

The Human Resources Management function in a way that makes decisions for the benefit of the people of the whole company every day that have the potential to be of high risk for their organizations. One of the core reasons for this need for risk mitigation is that indeed humans are not mechanical objects with a propensity for data-only decision making. Human beings have intuition, emotions, feelings, beliefs and experience which intermingle with their cognitive processes and have an impact on their decisions and actions (Rostomyan, 2012, 2015).

All this comes to suggest that human resources management is more complex than one can think, which comes to prove that to be an agile CHRM one has to have a huge set of capabilities to be able to lead the team successfully towards a common goal.

V. The Usage of Emotional Intelligence in Human Resources Decision Making

In the past, emotions and intelligence were often viewed as being in opposition to one another. Whereas, in the recent decades, researchers exploring the role of emotions in psychology have become increasingly interested in their cognitive nature.

In today’s globalized and digitalized world there is way too much stress which is a disturbing noise playing in the background of and hindering the successful decision-making processes.

In this respect, truly, emotional intelligence (EQ otherwise called EI) can be considered to be one of the cornerstones of success for any organization, big or small, since people, who make up the whole company, are not fully devoid of different emotions and feelings, beliefs and desires, motivations and aspirations, all of which influence the decision making processes.

The notion of emotional intelligence (EQ) was introduced and popularized to science by Daniel Goleman, an American psychologist, when he in his book “Emotional Intelligence” (1995) completely debated the nature of emotions and asserted that sometimes EQ may even matter more than IQ, since human nature comprises emotions, which are also evident in decision making processes and at workplace within the business world as well.

To elucidate the different processes behind EQ, D. Goleman (1995) developed a performance-based model of EQ to assess employee levels of Emotional Intelligence, as well as to identify areas of improvement. The model consists of five components, briefly stated below:

1. Self-awareness

Here, the author means that people are aware of their very own emotions and feelings and are comfortable with them. So, this first step of understanding your emotions and having a clear-cut idea of your very own emotions by means of self-reflection is the first ladder towards a high emotional intelligence.

2. Self-regulation

This second step towards a high EQ is being able to regulate those very emotions and feelings recognized and understood by you. This is especially important at workplace conditions, where we are a part of the whole and have to act accordingly, which also presupposes a proper regulation of your very own emotions, especially the outward expressions of anger due to emotional labor requirements.

3. Internal Motivation

Being driven by only financial causes or material rewards is not a beneficial characteristic feature, according to D. Goleman. A distinct passion driven by internal motivation for what you do is far better for heightening your emotional intelligence. This leads to sustained motivation, clear decision making and a better understanding of your organization’s aims, which very often in turn lead to better labor output and enhanced success of the whole company in general.

4. Empathy

Not only must we understand our own emotions, but understanding and reacting to the emotions of others is also very essential, since we do not exist on our own, especially within organizations, where we have to interact and cooperate with others. Identifying a certain mood or emotion from a colleague or client and reacting to it can go a long way in developing a strong relationship, which will resultantly lead to improved communication and better business results.

5. Social Skill

In fact, social skills are more than just being friendly. D. Goleman (1995) describes them as “friendliness with a purpose”, meaning everyone is treated politely and with respect, where healthy relationships are then also used for personal and organizational benefit. This includes also social awareness, which is the most important milestone in building successful relations, both at the workplace and in our private lives.

So, as we can see, Emotional intelligence in the workplace begins from the inside out with each individual. It involves recognizing various aspects of your very various feelings and emotions about people and different phenomena and other external stimuli and taking the time to work on the elements of self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, empathy and social skills.

The psychologists Peter Salovey and John D. Mayer (1990), two of the leading researchers on the topic, define emotional intelligence as the ability to recognize and understand emotions in oneself and others. This ability also involves using this emotional understanding to make decisions, solve problems, and communicate with others.

According to Salovey and Mayer (1990), there are four different levels of emotional intelligence:

- Perceiving emotions

- Reasoning with emotions

- Understanding emotions

- Managing emotions

All these aforementioned processes make up the groundings of emotional intelligence, which guides us in our everyday activities, both in our private lives and in business. According to D. Goleman, employees and their leaders, when identifying the greatest challenges their organizations face today, mention the following concerns (2003, p.5):

• People need to cope with massive, rapid change.

• People need to be more creative in order to drive innovation.

• People need to manage huge amounts of information.

• The organization needs to increase customer loyalty.

• People need to be more motivated and committed.

• People need to work together better.

• The organization needs to make better use of the special talents available in a diverse workforce.

• The organization needs to identify potential leaders in its ranks and prepare them to move up.

• The organization needs to identify and recruit top talent.

• The organization needs to make good decisions about new markets, products, and strategic alliances.

• The organization needs to prepare people for overseas assignments.

In this respect, especially when speaking about people working together more effectively, harmoniously and successfully, we can state that EQ plays a very vital role, since dealing with our very own emotions as well as the emotions of the other, has the greatest potential of driving us towards success, as people generally do not perform at their best when under stress or in an emotionally unhealthy and negative atmosphere.

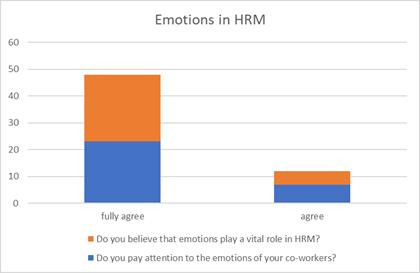

In the quantitative analysis survey conducted across some large companies in Germany, the question whether the managers occupying leading positions within the company pay attention to the importance of EQ skills at their workplace was researched. The results are hereinafter illustrated in Exhibit C below.

Exhibit C: Managers on emotions in HRM (Rostomyan, 2021).

As the illustration above of Exhibit C truly shows, managers in Germany are well aware of the importance of emotions at the workplace and their relevance in HRM, since none of them replied with a “no” and most of them fully agree on the importance and participation of emotions within the companies. Therefore, they have begun to pay more attention to the emotions of their co-workers to ensure a harmonious and successful interaction between them at the workplace amongst the colleagues, especially in these times of hybrid work from the premises of the home office.

Emotional intelligence impacts a number of important aspects in Human Resources both from an employee experience perspective as well as a functional leadership perspective.

1) Headhunting and recruitment

2) Performance Evaluation

3) Development of talent

4) Innovation and employee experience

5) Productivity

Here, it should also be noted that celebrating the co-workers’ big and small achievements is also an indicator of a high EQ of the manager, which should widely be applied within human resources processes, as in that case the employers will feel more emotionally secure, which will consequently raise their labor output and performance within a company that cherishes their personal growth and success.

Indeed, keeping the people involved within an organization and paying attention to their emotions has immense potential to boost motivation, productivity and innovation of work product as well as overall satisfaction and happiness. Besides, keeping an open ear to their doubts and concerns can also contribute to the success of the company, since people who share their views and concerns with others will together with the management look for sustainable solutions and make the decision-making processes smoother and healthier.

When speaking about emotional intelligence, it is important to note that there exists another notion very close to EQ relevant for the workplace, namely “emotional labor”. This term was first coined by A. Hochschild (1983), which means that people have to act in a certain manner according to their vocations. For instance, the customer service assistant or the flight attendant have to keep a smiling face even under emotionally heated circumstances with the customers.

In this connection, it should be noted that quite recently another significant finding has been made in science, namely Peter Spiegel proposing the notion of WeQ, which concerns collective decision making and collective intelligence (Rostomyan, Rostomyan & Tèrnes, 2021). This notion of WeQ can also be linked to EQ and we may assert that a person with high EQ skills can collaborate more easily with the others, thus raising the overall WeQ. This can largely be applied in decision making processes, especially big bet decisions, where due to WeQ, the participating parties will have the ultimate chance of meeting the right decision, which is of high-stake nature and greatly impacts the whole company.

As can be seen, emotions, emotion management and emotional intelligence are a part and parcel for the overall success of the whole company, as well as for individual success and peaceful and harmonious interrelations with the social workplace where people continually interact with each other and cooperate with one another. Where managers ensure an emotionally healthy, psychologically safe atmosphere, they will in turn see improvements and better results in both decision-making processes and overall performance.

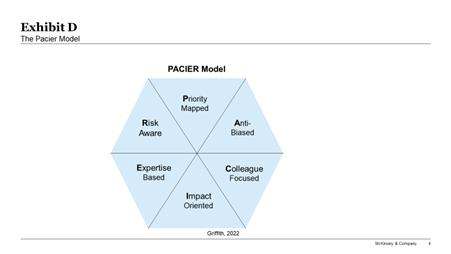

In order to help foster success within the decision-making processes at the company level, below is a newly developed model by us which will help to bring consistency and clarity to often complex human-centered decision making. This model, called PACIER, makes decision making more rational by taking into account very important factors that rely on both IQ and EQ.

VI. A Novel Model for Human-centered Decision-making: PACIER

As demonstrated and discussed above, decision making presents a significant opportunity for an organization when executed appropriately and in consideration of all relevant levers. For any organization, whether in growth, acquisition, reorganization or even in steady state, the Human Resources function should have a clear and consistent decision-making framework to apply across all four archetypes of decision. The application of a consistent decision framework can help to manage the challenges that are outlined relative to HR decision making.

In order to address common Human Resources challenges, the PACIER model was created to include the 6 elements demonstrated in Exhibit D. The intent of the model is that in any of the four decision archetypes, each of the six elements are considered carefully whether by an individual in an empowered decision or by a group in a collaborative decision process. The individual or group should ensure that they have appropriate input and expertise available to have clear thinking on each topic. The six PACIER dimensions are drawn from research related to broad decision making, specific challenges in Human Resources and effective balance of intuition and data-based decision making.

Exhibit D: PACIER Problem Solving and Decision Method

The six levers of the PACIER model are shortly described below:

1. Priority Mapped: In a rapid growth, hyper VUCA world as discussed by Dr. Hitendra (Columbia University Executive Education, 2020) it is important that enterprise level goals and priorities are considered in problem solving and decision making. This requires a level of communication from leadership that makes clear what priorities are and to what extent any individual can veer from those priorities. In a larger organization, delineating what priorities and decisions can be made locally and which must be guided more globally is helpful. Having a strategic human resources plan mapped to a set of global business priorities additionally assists in making decisions. Both quantitative analytics and qualitative evidence are most often used to ensure that decisions are mapped to business level priorities. In particular for decisions that are longer term and engage a broad range of stakeholders, this lever should receive persistent attention.

2. Anti-Biased: As discussed above, bias is one of the more dangerous pitfalls for excellence in decision making, in particular in human related decision making. Because bias is so deeply ingrained in the human psyche, it is also a very sticky issue for decision makers. Identification of biases in decision making can be resolved in more simple decisions through adherence to policy or through use of data sources and analysis. However, for decisions that are more emotionally charged and intuition based such as a dispute between employees, biases are often more difficult to identify and resolve. In order to ensure problem-solving or decision-making that is as free from bias as possible, raising awareness and constantly ensuring that the topic of bias is considered is critical. Debiasing decision making can be done in multiple ways beginning with understanding and analyzing past decisions for bias (Baer et al., 2020). Leveraging people who are trained in spotting biases can be helpful in working to make decisions objective when there is the known subjective layer of bias, in performance reviews for example.

3. Colleague focused: In the struggle for balance between data and intuition-based decisions, in particular in longer term HR strategic decision making or rapid decision making, a focus on colleagues can be lost or deprioritized. The result may be a policy or process or even significant global priority that is incongruous, complicated or even harmful to individuals. While an unintended consequence, colleagues struggling with a new process is not an ideal outcome. This is in direct contrast to the research by Hill and Tedards (2021, online). Considering the impact on the satisfaction, connectivity, time and balance of colleagues should be part of every decision-making process in order to mitigate the risk that solutions are not implementable or that they are done so at the expense of another colleague. As an example, a decision could be made to offer an early retirement package without consideration for the impact of the messaging on colleagues who may read such a program proposition as an attempt to wrongfully eliminate older employees from the workforce rather than an exciting privilege as it may have been intended.

4. Impact oriented: In HR decision making, often there is a clear impetus for a decision to be made. A need for integration of people in an acquisition, a need for large scale reorganization, a request to have an individual's compensation re-evaluated, an employee conflict or issue, a request to design a new performance management process - to name a small set. Impactful decision making, therefore, means something different in the HR space than in the broader business sense. Impactful decisions are those that have a positive impact on individual people and that contribute to the business objectives. Impact that should be considered when using the PACIER model should include financial impact, risk impact, people, even impact on broader society. For example, in the closing of a production plant the HR decisions around the process of layoffs of the employees at that plant could have a significant impact on the individual’s long-term benefits, on the broader community, even on the reputation of the organization.

5. Expertise Based: When problem solving and decision making are underway it is important that the most credible stakeholders who hold true knowledge is gathered in order to devise the most innovative and practical solutions. In the case of Human Resources decision making, this could mean gathering external experts such as firms experienced in compensation benchmarking or in conducting broad searches for benefits providers. Leveraging expertise of the people in a relevant business is also important. For example, engaging a person with an in-depth understanding of the marketing function will be helpful in discerning the rationale behind a reorganization of that department.

6. Risk aware: Risk management is a topic which has become increasingly central to most of the organizations as the complexity of the work and legal environments around the world have increased. However, in Human Resources decisions, risk management is also central. While legal and corporate risk is a clear and important factor, reputational risk and employee engagement risk are also among important risk factors to take into consideration. For example, in decisions about a compensation topic, supporting a certain employee through donations, creation of a new affinity network, even termination of the contract with an employee, risk should be considered from multiple perspectives. Because full risk evaluation can appear to be a barrier to rapid decision making, in short term empowered or leadership decisions, full risk analysis is often neglected.

The PACIER Model is most effective if used at the start of any decision-making process, since when initially faced with a problem for solution, the PACIER model may be helpful in brainstorming and checking assumptions to ensure that each dimension is included and integrated into any brainstorming or proposed solutions. It could even be that each dimension of the model is posted and used as anchors for brainstorming and creating new, innovative thinking. Using PACIER maps as discussed in detail below is part of creating a solution set that will help to simplify and streamline decision making at the same time as it adds rigor and consistency to the same. For decision making the PACIER model will help a decision team or an individual decision maker to ensure that all critical areas are considered - from colleague care to risk to bias minimization.

Our proposed new PACIER model is simple and intelligible but also opens minds to innovation and to applying collaborative rigor to the decision process by allowing for the design, consideration and decision between a broad range of possible solutions that are tested against a consistent set of six process anti-biased levers. Each lever of the model enables improved collaboration and rapid innovation and therefore over time, Human Resources decision making will continue to improve until it is organically collaborative and consistent in nature. Specific process and use of this approach are described in the following subsection.

VII. Application of The PACIER Model to Sharpen Human Centered Decisions

Since the PACIER model will be utilized for Human Resources decision making across the four key decision types, a particular focus on engagement of critical stakeholders and an open approach to developing multiple solutions prior to landing on a single solution. In particular, in empowered decisions where there is more autonomy, it may be difficult to embrace the concept of acting using a model and data above majority intuition, but this is exactly the gap that the PACIER model will help to close.

Often an HR leader or even the whole HR team may be stuck, either on a single solution or without any solution to a certain question. In order to use the PACIER model, thought starter questions can help to advance thinking individually or collectively upon a certain question or towards the solution of a particular problem. Such questions on each dimension should be expanded relative to the specific issue in consideration. While not a comprehensive listing of every question that could be asked along each dimension of the PACIER model, the below provides some examples of questions that could be posed in any of the four decision models:

P - Priority Mapped: What solution might be consistent with priorities for our people? Does this decision enable other organizational priorities? Would communication of this decision make sense to colleagues relative to other previously communicated priorities?

A - Anti-Biased: Has a broad group of colleagues beyond “the usual suspects” been engaged? What potential biases could come into play in making this decision? Have multiple alternative solutions been considered from different people’s points of view? Has the decision been sense-tested with other colleagues?

C - Colleague focused: What colleagues would be most and least impacted by the solution? Would the solution cause a burden to any colleague group more than another? Is the solution equitable for all colleagues? Will this decision be consistent and simple for the benefit of all the colleagues to understand / is there a way to simplify this decision communication?

I – Impact-oriented: Is this solution set maximized for impactful and meaningful change at the appropriate scale and scope? Has the impact across different parts of the organization been considered (ripple effect)? Is there a solution that would be more impactful to the bottom line or mission of the organization?

E - Expertise Based: Have internal and external experts been engaged as needed? Are internal experts in agreement with the proposed approach or solution? Is a sufficient balance of data and intuition involved in the development of the selection of an option? What would a pure data based / intuition-based solution be? What will be the profit of this engagement?

R - Risk Aware: Have legal and reputational risks been considered? Are high risk areas sufficiently vetted with relevant stakeholders (legal, technology, education, business, etc.) Are risk and reward sufficiently balanced? What will be the cost of this affinity?

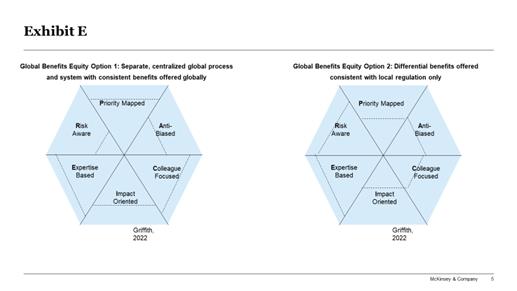

Working through this complicated and sensitive issue with consideration for legal variability around the globe could begin with solution generation and consideration of the PACIER model’s dimensions to help instill creativity and expertise into the generation of multiple solutions, even prior to decision making. For example, along the lever of ‘Priority Mapped’ the discussion may be around defining ways in which the equalization of benefits is consistent with larger organizational priorities. Along the lever of ‘Risk Aware’ the discussion may be around how to resolve issues with local country medical plans that prohibit access for same sex partners or other benefits related to this population. After an unbiased discussion of all six levers, the solution space may have multiple non-viable solutions and multiple viable solutions. Above all, the group will have collaboratively created a set of comprehensive alternatives to consider in the decision-making process.

The group will then create a simple PACIER Map for each viable solution to be presented or to be considered for decision. The PACIER Map as demonstrated for this example in Exhibit E is simply a depiction of the PACIER model with each lever’s analysis summarized by a simple line. For a collaborative decision such as provided in this example, the mapping itself need not be a time intensive activity but rather a collaborative and discussion-based way to create a graphic depiction of the results. In the specific example of global benefits equality, Exhibit E presents two options. It is clear from the comparison of these simple PACIER maps that there are tradeoffs that must be considered in the decision-making process. Without leveraging this model, generally the answer to this complex issue may be “local benefits only”. While this may indeed be the answer after evaluation, the PACIER model provides the option to analytically, visually and intuitively make this evaluation.

Exhibit E: Comparative PACIER Maps for Global Benefits Equality

Depending on the complexity of the decision to be made, there may be a very broad solution represented by multiple maps or only a few maps according to our proposed model:

1. Gather PACIER maps and descriptions of all viable solutions.

2. Bring together relevant decision makers for the appropriate decision type based on the need - urgent vs. long term and individual vs. collective.

3. Determine the potential need for weighting any of the six dimensions. For example, legal risk may have more weight than priority mapped in some human related decisions.

4. Discuss collectively or reflect individually on each dimension of the model.

5. Determine which solution maximizes the greatest number of PACIER dimensions with consideration for the weighting discussed in step 3.

6. Consider any additional external factors. The PACIER model includes the leverage of external expertise, but additional external factors that may be important should be considered. Some examples of external forces may be governmental instability, previous precedent, leadership transition among many others which may be relevant depending on the specific solution set.

7. Should multiple options be considered after this analysis, determine which of the PACIER dimensions are top priority and further narrow options accordingly.

To illustrate this process, consider a continuation of the example above around the global equalization of the exclusion of minority, race and religious groups. In this case, risk (R) and colleague focus (C) may be very important to trade off against each other. The second solution indeed may introduce some degree of bias and be less colleague focused because benefits become inequitable across employees; however, the solution also mitigates risk that may or may not be the most important factors to the organization.

Human Resources decisions have typically been made using a combination of data based, historical precedent and intuition-based decision making. Adding the PACIER model adds discipline and rigor to graphically visualizing tradeoffs among six areas that research suggests are critical for business decision making. Using this disciplined model ensures a fulsome view of factors important to the organization in general and ensures appropriate individual reflection in empowered decisions and appropriate collaboration in larger group decisions with multiple stakeholders.

VIII. Discussion

In order to use the innovative and insightful PACIER model, the initial intent should be clear. The model is not designed to force a multi-hour discussion related to each of the six elements for every single problem or decision, rather as a set of levers for evaluation and consideration to ensure that all critical areas have been considered in the process of decision making that will influence the overall well-being of the employees, as well as the whole company, and therefore, the right people and considerations have to be taken into account. The model may be a useful process guide, starting point or ending checkpoint. For example, if there is a decision about headcount allocation to be made, the team may devise a set of solutions and at the end, refer to the PACIER model and review each element to ensure that they have thought through every element.

IX. Conclusion

The Human Resources function in organizations of every size and scope is evolving rapidly and taking on increasingly complex, risky topics which are core to the operations of the business. Institutional memory and historical precedent are no longer sufficient approaches to making modern decisions in this rapidly evolving legal and human-centered business environment.

Truly, the evolution of advanced analytical capabilities affords HR professionals the ability to identify trends across time and populations, but does not eradicate the need for human based intuition and emotional intelligence in decision making, especially when making decisions that impact the lives of other human beings and even the broader business and society.

Because the HR no longer sits on the sidelines as significant decisions are made, the function is now responsible for a meaningfully massive range of topics that call on deep decision-making skill sets. Some of these skills may be as simple as relying on intuition, understanding trends, getting coaching or even simply asking for a second opinion, however, there is not currently a broadly accepted, rigorous method of analyzing the range of human-centered decisions that need to be made. With the advent of the PACIER model, decisions that are made both for individuals and for large groups as well as those with shorter term impact and those with longer term impact are considered through six different lenses.

Since the field of Human Resources continues to grow and mature, so do the skill sets of practitioners and the approaches used to consider problems and make decisions. The past decades have truly witnessed the evolution of Human Resources from a back-office operation within the fields of business operations. Thence, such tools and techniques like the PACIER that provide thoughtful, clear and consistent approaches and help make meaningful ideas come to life, hold the promise to ensure that organizations improve the satisfaction, innovation and performance of the people at the heart of those very organizations.

X: References:

Adams, L. (2021). HR Disrupted: It’s time for something different (2nd Edition) (Updated ed.). Practical Inspiration Publishing.

Baer, T., Heiligtag, S., and Samandari, H. (2020, September 16). The business logic in debiasing. McKinsey & Company. Available at https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/risk-and-resilience/our-insights/the-business-logic-in-debiasing

Betterworks (2021, November 22). 8 of the Biggest Challenges for HR in 2021. Betterworks. Available at https://www.betterworks.com/magazine/8-of-the-biggest-challenges-for-hr/

Buhler, P. (2002). Human Resources Management. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Cherniss, C. and Goleman, D. (2003). The Emotionally Intelligent Workplace. San Francisco: Jossey Bass. A Wiley Company.

Columbia University Executive Education. (2020, November 24). Reimagining Leadership for the New World of Business. Available at YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gL2mHKYgqds

Dearborn, J., and Swanson, D. (2017). The Data Driven Leader. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley.

Decision making in the age of urgency. (2021, March 1). McKinsey & Company. Available at https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/people-and-organizational-performance/our-insights/decision-making-in-the-age-of-urgency

de Smet, A., Lackey, G., and Weiss, L. M. (2021, March 1). Untangling your organization’s decision making. McKinsey & Company. Available at https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/people-and-organizational-performance/our-insights/untangling-your-organizations-decision-making

Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional Intelligence. New York, Toronto, London, Sydney, Auckland: Bantam Books.

Hill, Tedards et al. (2021, December 13). Drive Innovation with Better Decision-Making. Harvard Business Review. Available at https://hbr.org/2021/11/drive-innovation-with-better-decision-making

Hochschild, A.R. (1983). The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. Berkeley: University of California Press.

HRCI. (2018). The State of HR Skills and Education. Bamboo HR.

Khan, N., Millner, D., and Marr, B. (2020). Introduction to People Analytics: A Practical Guide to Data-driven HR (1st ed.). Kogan Page.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York, NY: Farrar, Strauss & Giroux.

Kahneman, D. (2021, May 25). Why Smart People (Sometimes) Make Bad Decisions. Harvard Business Review. Available at

https://hbr.org/podcast/2021/05/why-smart-people-sometimes-make-bad-decisions

Kippenberger, T. (2002). Leadership Styles. Oxford: Capstone Publishing.

Kumari, N. and Singh, D. (2019). Leadership Styles and impact on employees’ organizational commitment. Beau Bassin. Scholar’s Press.

Lawler, E. and J.W. Boudreau (2009). Achieving Excellence in Human Resources Management: An Assessment of Human Resource Functions. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Manoogian, J. (2018). Cognitive Bias Codex. Wikimedia.Com. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cognitive_bias_codex_en.svg

The Psychology Behind Why We Strive for Consensus. (2020, November 12). Verywell Mind. Available at Available at https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-groupthink-2795213

Rostomyan, Anna (2012). The Vitality of Emotional Background Memory at Court. Berlin: DeGruyter.

Rostomyan, Anna (2015). The Impact of Emotions in Decision making Processes in the Field of Neuroeconomics, New York: Academic Star Publishing Company.

Rostomyan, Anna (2020). Business Communication Management: The Key to Emotional Intelligence. Hamburg: Tredition.

Rostomyan, Anna, Rostomyan, Armen and Anabel Ternès von Hattburg (2021). “The Significance of Emotional Intelligence in Business”, International Business and Economics Studies Journal, Vol 3, No 3, LA: Scholink Publications. Available at http://www.scholink.org/ojs/index.php/ibes/article/view/3970

Roth, E. (2021, September 13). 5 Steps to Data-Driven Business Decisions. Sisense. Available at Available at https://www.sisense.com/blog/5-steps-to-data-driven-business-decisions/

Salovey, P. & Meyer, J. (1990). Emotional Intelligence. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 9(3), 185–211. Available at https://doi.org/10.2190/DUGG-P24E-52WK-6CDG

Schermuly, C. (2021). New Work - Gute Arbeit Gestalten: Psychologisches Empowerment von Mitarbeitern. Berlin: Haufe.

Talentedge. (2021). Decision making in Human Resource Management. Available at https://talentedge.com/articles/human-resource-management-decision-making/

Tipton, M. (2018, January 21). The Importance of Precedent. Why HR. Available at https://whyhr.guru/the-importance-of-precedent/

Tippet, E. (2021, August 31). 10 Ways to Mitigate Bias in Your Company’s Decision Making. Harvard Business Review. Available at https://hbr.org/2019/10/10-ways-to-mitigate-bias-in-your-companys-decision-making

Transcending Either-Or Decision Making. (2020, April 8). Harvard Business Review. Available at https://hbr.org/podcast/2017/09/transcending-either-or-decision-making

Wright, P.M. and Paauwe, J., Guest, D.E. (2012). HRM and Performance: Achievements & Challenges. West Sussex: Wiley.